Oh come, let us sing to the LORD;

let us make a joyful noise to the rock of our salvation!

Let us come into his presence with thanksgiving;

let us make a joyful noise to him with songs of praise!

For the LORD is a great God,

and a great King above all gods.

In his hand are the depths of the earth;

the heights of the mountains are his also.

The sea is his, for he made it,

and his hands formed the dry land.

Oh come, let us worship and bow down;

let us kneel before the LORD, our Maker!

For he is our God,

and we are the people of his pasture,

and the sheep of his hand.—Psalm 95:1–7

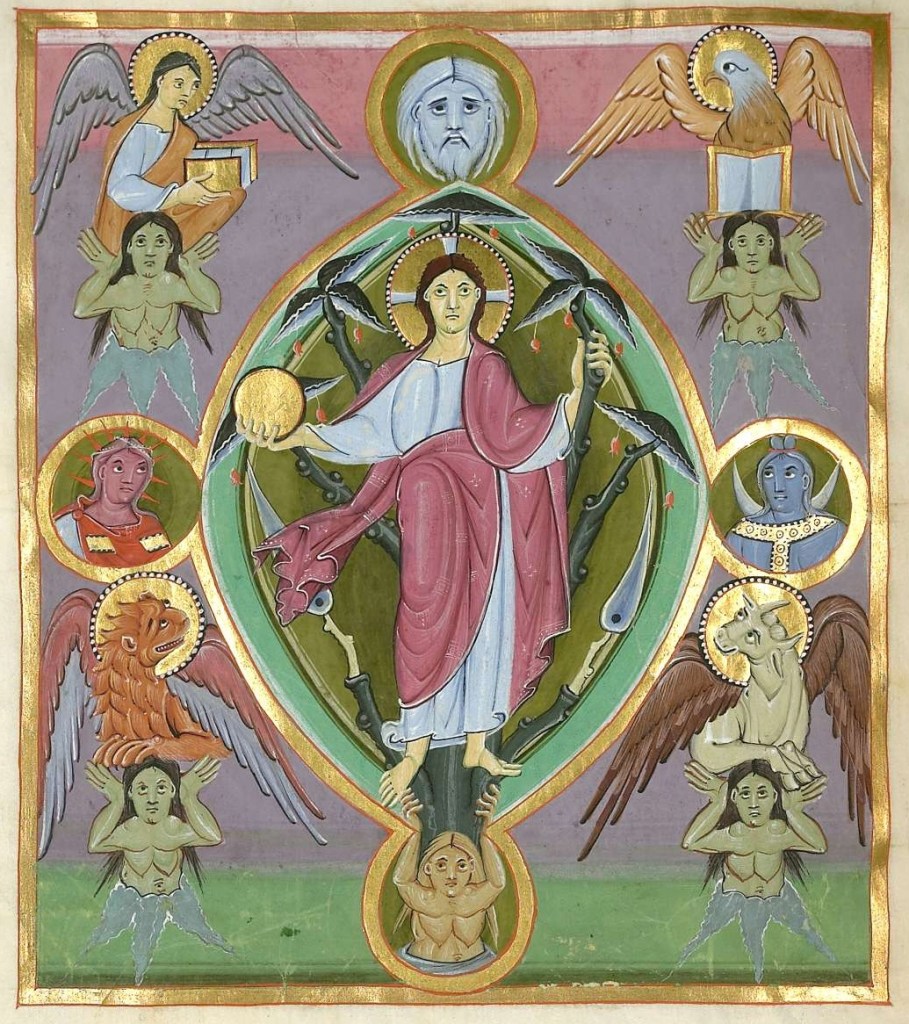

This is the Psalm reading for the last Sunday of the liturgical year, Christ the King Sunday. I’ve paired it with an Ottonian miniature from around 1015, which shows Christ, framed by a mandorla (an almond-shaped aureole), standing in a branched tree of life. The gold-leaf outline of this glory cloud encompasses heaven (Caelus, the top figure) and earth (Terra, aka Terrus, at bottom), two realms connected by Christ himself. (Earth is his footstool! That is, part of his throne.) He holds a globe in his right hand and is surrounded by symbols of the four evangelists (the tetramorph)—each supported by a water nymph representing one of the four rivers of paradise—and Sol (sun) and Luna (moon). I love how this image emphasizes the life-giving nature of Christ’s rule, and how it extends over all of creation.

From our limited human perspective, it can be hard to see the divine reality that this artist is pointing to. It sometimes doesn’t feel like Jesus is on the throne, holding together everyone and everything in love. But I look at that little orb, and I think of all the sin and suffering and love and grace and stress and beauty swirling around in that one small part of the cosmos, and I see that it’s rendered in precious gold, and is gripped firmly by the hand of God, who—zoom out—is “a great King above all,” who made the heights and the depths and who gives us his word and indeed his very self, a tree of life for the healing of the nations. As we head into Advent, may we not lose this vision of the Christ who reigns.

More about the art: In the tenth and eleventh centuries, the Benedictine abbey on the island of Reichenau in Lake Constance in southern Germany was the site of one of Europe’s largest and most influential schools of manuscript illumination, known as the Reichenau school. The painting above is from a Gospel-book produced there, commissioned by Holy Roman Emperor Henry II (r. 1002–24) for the cathedral he founded in Bamberg. The book is now housed at the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek (Bavarian State Library) in Munich, along with two other similar illuminated manuscripts from Bamberg Cathedral: the Gospel-book of Otto III (Clm 4453) and the evangeliary of Henry II (Clm 4452). Find out more about this particular manuscript at the World Digital Library. You can also browse the images here by selecting the links in the “Content” sidebar at the left.

For other artworks from Art & Theology that show, in a literal manner, “the whole world in [God’s] hands,” see this medieval Pisan fresco with signs of the zodiac; How God loves his People all over the World by John Muafangejo; Creation of the World by Lyuba Yatskiv; Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci, a common image type; and a Florentine panel painting of God the Father.

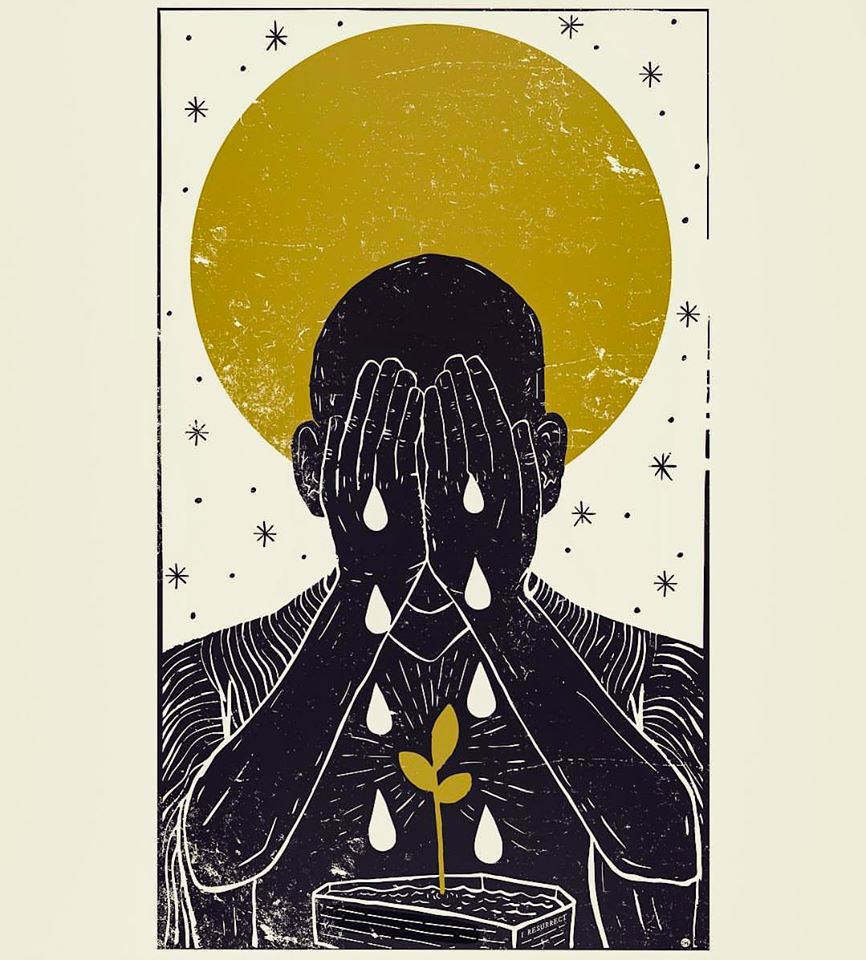

Do you know of any good nonliteral images that say to you, “The world is in God’s hands”? That is, a visual artwork that helps you sense God’s sovereignty? I often fall back on traditional visual conceptualizations of theological teachings like this, but I’d like to expand my repertoire!

+++

SONG: “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands,” African American spiritual

There are hundreds of professional recordings and live performance videos of this traditional song. It was first published in the paperbound hymnal Spirituals Triumphant, Old and New in 1927 and became an international pop hit in 1957 when it was recorded by thirteen-year-old English singer Laurie London.

First off, I want to feature a fairly recent two-part video compilation released by TrueExclusives. Back in March, as the first wave of the coronavirus hit the US, Tyler Perry posted a video of himself singing one verse of “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands” to provide a word of assurance in the face of rising death tolls and social isolation. He called on his fellow musicians and other friends to likewise video-record a verse or two, in whatever key or style they wished—just a simple, unpolished phone recording—tagging it #tylerperrychallenge. These were then collected into two videos, a string of contributions from people like Mariah Carey, Usher, Patti Labelle, Jennifer Hudson, Shirley Caesar, LeAnn Rimes, Aubrey Logan, Israel Houghton, and many more. For a list of all the singers with time stamps, see the comment by YouTube user benzmusiczone for the first video and the comment by The Cherie Amour Show for the second.

(Update, January 2023: The original two YouTube videos from the TrueExclusives channel have been removed—not sure why—but you can view the originals on Tyler Perry’s Facebook page: part 1 and part 2.)

Some participants sing in other languages—for example, Nicole Bus in Dutch, Jencarlos Canela in Spanish. Others adapt the lyrics to more specifically address the context of our global pandemic. Kelly Rowland, for example, sings, “He’s got the doctors and the nurses in his hands.” Stevie Mackey names specific countries and virus hot spots. And not only does God have the itty bitty babies in his hands, Ptosha Storey reminds us; he also has the elderly. BeBe Winans spans the cosmic to the small in his verse, emphasizing that God’s sovereign care is both expansive and intimate: “He’s got the moon and the stars in his hands / He’s got Pluto and Mars in his hands / And as I’m sitting in this car, I’m in his hands / He’s got the whole world in his hands.”

I love me some harmonies, so I particularly enjoyed hearing sisters Chloe and Halle Bailey (2:32) and The Walls Group (16:54).

What follows are a handful of other renditions I want to highlight.

Jeanne Lee [previously], 1961:

Ruth Brown, 1962 (classic gospel):

A live 2006 performance in Johannesburg—with hand motions!—by the African Children’s Choir:

A lush choral and orchestral arrangement by Mack Wilberg, featuring Alex Boyé [previously] and the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, from 2010:

Similarly lush, a duet performed by operatic sopranos Jessye Norman and Kathleen Battle, backed by the Metropolitan Opera Chorus, the New York Philharmonic, and the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra. The performance was conducted by James Levine at Carnegie Hall in 1990 and is included on the album Spirituals in Concert (1991). The arrangement is by Robert de Cormier:

This post belongs to the weekly series Artful Devotion. If you can’t view the music player in your email or RSS reader, try opening the post in your browser.

To view all the Revised Common Lectionary scripture readings for Proper 29 (Reign of Christ), cycle A, click here.