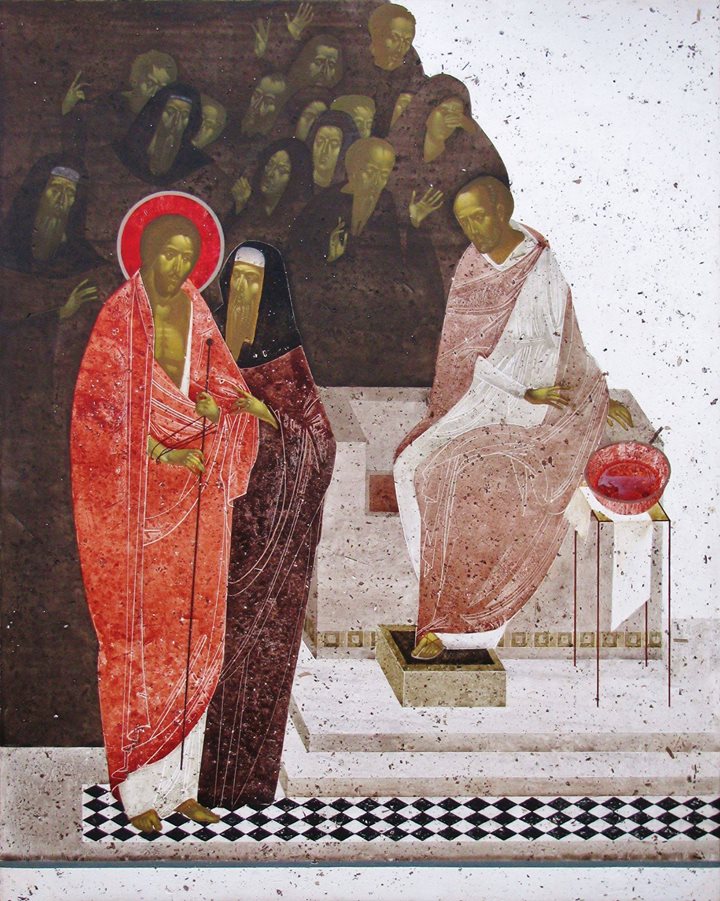

VISUAL MEDITATIONS (ARTWAY.EU)

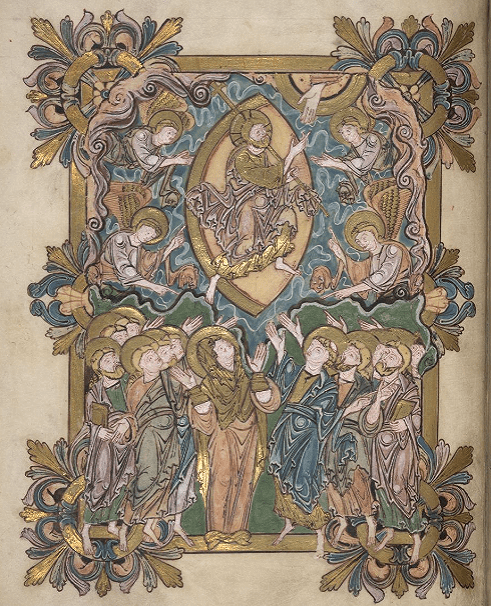

Jonah Swallowed and Jonah Cast Up, commentary by Victoria Emily Jones: My latest visual meditation for ArtWay was published Sunday—it’s on two third-century Jonah sculptures from Asia Minor that likely decorated a family fountain. Early Christians read the story allegorically (at least on one level), as pointing forward to the death and resurrection of Christ. The “great fish” is portrayed as a ketos, a sea-monster of Greek myth.

Run by Marleen Hengelaar-Rookmaaker, the faith-based website ArtWay has been publishing a new visual meditation every Sunday for years, as well as a lot of other content from a variety of contributors. To subscribe to the weekly email, click here. Here are just a few VMs published in the past year that I particularly enjoyed:

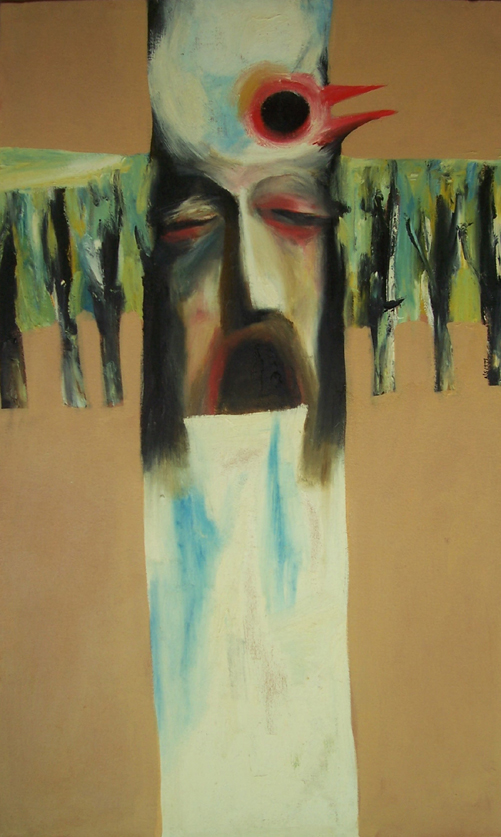

Manu-Kahu by Brett a’Court, commentary by Rod Pattenden: Pattenden begins, “This striking image of an airborne Christ is from New Zealand painter Brett a’Court. It is part of his investigations into a way of bringing together the spiritual insights of the indigenous culture of the Maori people and that of Christianity brought to New Zealand by British settlers. In cultural terms it is a hybrid image. This is something that occurs when two cultures are in a process of mutual re-assessment. That sort of conversation is full of conflict and critique but also allows for the potential for new forms to arise that express the best of both traditions. A Christ figure flying in the sky like a kite, is such a form. It is a new thing, a potential heresy or aberration, but one full of potential for new insight and spiritual refreshment.”

Knife Angel by Alfie Bradley, commentary by Rachel Wilkerson: This twenty-seven-foot-tall sculpture, welded from 100,000 knives collected in confiscations and amnesties around the UK, confronts the issue of knife violence. The artist cleaned and dulled the blade of each knife he received and engraved personal messages on all the wings’ “feathers,” messages sent by families affected by knife violence.

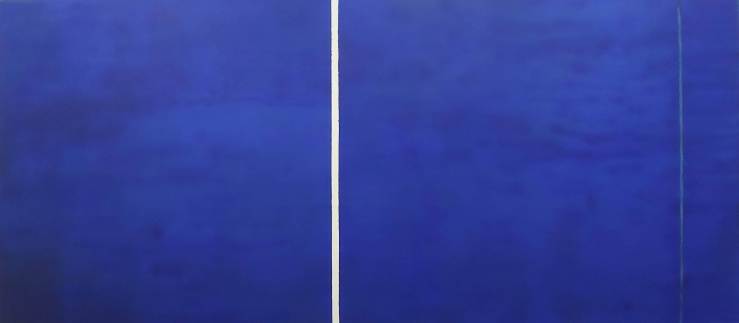

Cathedra by Barnett Newman, commentary by Grady van den Bosch: I saw this painting in Amsterdam last spring and was surprised by how it compelled me. (I don’t typically gravitate to abstract art.) After spending some time up close—I supposed this was a Newman, and Newman says his paintings need to be experienced up close—I looked at the label and saw that it has a religiously inflected title: Cathedra. The word is Latin for “seat,” and in Christianity it refers specifically to the bishop’s chair inside a church (churches that had a cathedra were called cathedrals). But Newman was of Jewish descent, and van den Bosch writes that Cathedra is meant to represent the throne of God. “And above the firmament that was over their heads was the likeness of a throne, as the appearance of a sapphire stone . . .” (Ezek. 1:26).

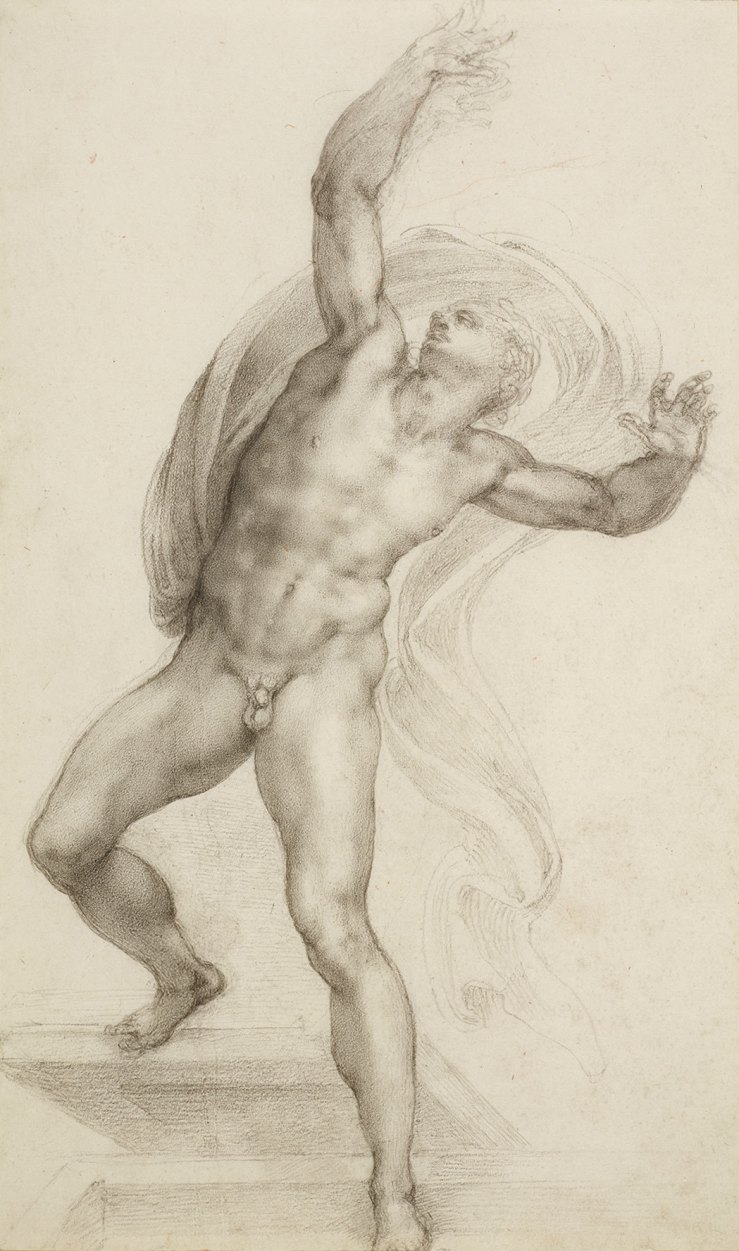

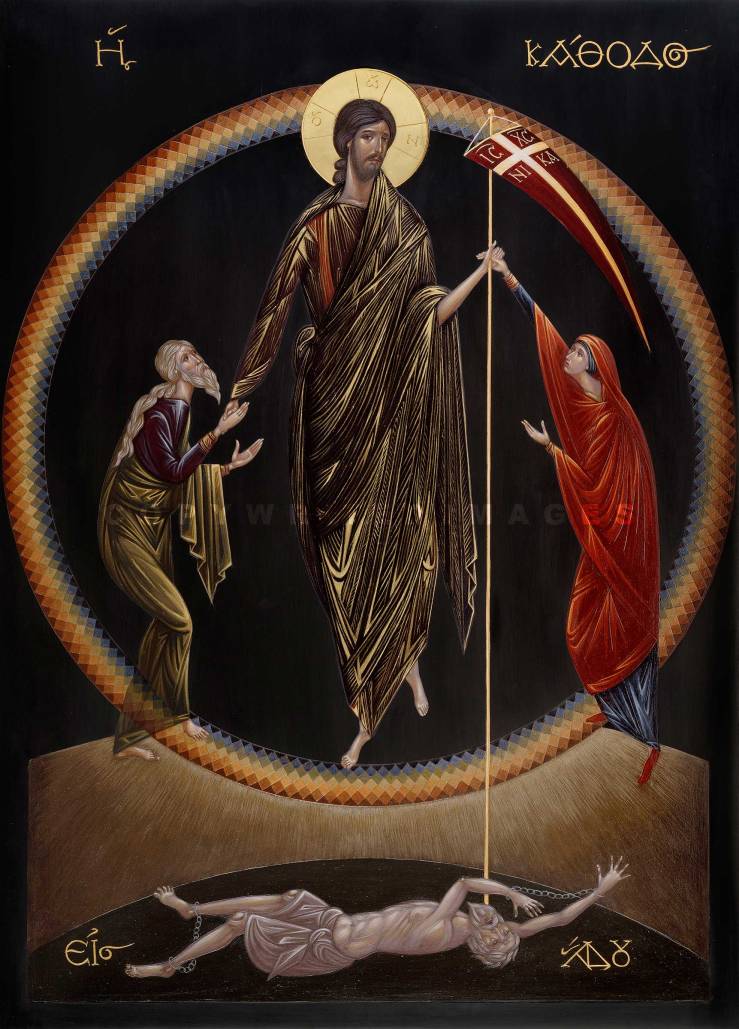

As someone who loves historical Christian art, including its many Christ Pantocrators, I must nevertheless admit that there is something so right about modern artists’ often apophatic approach to evoking the Divine. While I do believe God imaged Godself in the person of Jesus Christ and is therefore representable, I understand the argument some make that abstraction is a better visual language for spiritual subject matter or encounter. I accept both/and. Whether God is shown as a rich, blue expanse that invites and envelops, or a heroic nude emerging from the jaws of death, or a Man of Sorrows head with a harrier hawk’s body, I think we can learn a little something from the diversity of representations, which are not mutually exclusive. Not all representations need be embraced, but nor do unfamiliar, difficult, or even shocking ones need be automatically dismissed.

Click on the link for more on how to read Newman’s color field paintings, including his signature “zips.”

+++

FREE ONLINE COURSE: Watching TV Religiously: Through at least July 1, Fuller Theological Seminary is offering all its online Fuller Formation courses for free! I just finished taking Watching TV Religiously, taught by Kutter Callaway [previously], author of the book of the same title, and really enjoyed it. It’s a series of six self-paced lessons, which includes short video lectures by the professor, audio conversations with TV writer Dean Batali (Buffy the Vampire Slayer; That ’70s Show), TV watching assignments, reflection questions, and more.

The course aims to help Christians develop critical tools for watching television and a vocabulary that is as rich and thoughtful as the medium itself, so that we can engage it constructively. (It need not be mindless entertainment!) Callaway explores television as a technology, a narrative art form, a commodity, and a portal for our ritual lives. He’s interested in how stories are told in this episodic, audiovisual format, and what that means for the Story we tell. The course is not about what Christians should watch, but how Christians should watch, leaving ample room for individual viewers to set their own boundaries, ethical and otherwise. (Callaway acknowledges that TV can form as well as de-form us.) He discusses empathy building and access to other perspectives, knowing your sensibilities, how being offended can be useful, watching in community, seeing God in all places, being aware of how your desires and imagination are being shaped, Christians in Hollywood (and Christian characters on TV), and the culture shaping TV and TV shaping culture, among other things.

The course is fairly broad in its approach; it does not analyze particular shows or episodes, though some specific examples are mentioned in conversations, and students are encouraged to form discussion groups with friends or family members and apply what they’re learning to shows of their choice. I really appreciated the assigned PBS docuseries America in Primetime (somewhat outdated because made in 2011 but very good nonetheless), whose four episodes explore character types throughout the history of TV, from the fifties to today: “The Independent Woman,” “Man of the House,” “The Misfit,” and “The Crusader.” From taking this course I realized how many acclaimed TV shows I’ve never seen. I’ve got a lot of homework to do!

Other arts courses offered by Fuller Formation are

- Nurturing Your God-Given Creativity by Makoto Fujimura

- Healing Cultural Divisions Through Art, also by Makoto Fujimura

- Theology and Popular Music by Barry Taylor and Nate Risdon

+++

POEM: “My Mother’s Body” by Marie Howe, read with commentary by Pádraig Ó Tuama: As Mother’s Day is Sunday, I thought I’d share this wonderful, sad-sweet, mother-themed episode of the new Poetry Unbound podcast from On Being Studios. Pádraig Ó Tuama introduces Marie Howe’s “My Mother’s Body,” in which a middle-age woman, caring for her dying mother, thinks back to the time when her mother was just a twenty-four-year-old girl giving birth to her. The speaker in the poem is Howe.

She imagines being in her mother’s womb, experiencing the rhythm of her mother’s heartbeat. (What an exercise, to imagine yourself as your mother’s baby!) Now decades later, her mother is dying—that heart is failing, and the kidneys too. The uterus has been removed. Toggling between the two time frames, the poem is both a celebration of the strength of women’s bodies and a lament for its vulnerabilities, especially in old age. Howe marvels at how her mother’s body was capable of such a wonder as giving and sustaining life, and now to see that once-vibrant form breaking down grieves her. In some sense their roles have switched as daughter mothers mother, combing her hair, changing her soiled bedsheets.

The poem opens with “Bless my mother’s body” and ends with “Bless this body she made . . .” In the progression of pronouns in the last two lines—my, her, our—is a recognition of how our mothers always remain a physical part of us. They are in our cells. “My Mother’s Body” is a thank-you and a letting go.

The poem is from Howe’s collection The Kingdom of the Ordinary—which I highly recommend.

+++

ARTICLE: “5 Contemporary Poets Christians Should Read” by Mischa Willett: “There is so much good crop still being pulled from the fertile fields of theologically inflected verse,” writes poet Mischa Willett—so don’t stop short, content merely with Donne and Hopkins! This is an excellent short list of contemporary poets of faith, with summaries of key themes and recommendations for which volume(s) to start with. Willet was recently on The Ride Home with John and Kathy to discuss this topic, and he wrote a follow-up post on his blog.

+++

MUSIC VIDEO: “I Am a Poor Wayfaring Stranger”: One of the most poignant scenes in last year’s 1917 is when, after a harrowing journey across No Man’s Land, Lance Corporal William Schofield—exhausted, disoriented—reaches a wood and encounters a fellow British soldier singing the spiritual “Wayfaring Stranger” [previously] to a battalion that sits at somber attention, for they’re about to go into battle. This official music video from Sony splices together clips from the movie with studio footage of the actor and singer Jos Slovick.