PRAYER: “God, I Wake” by Rev. Maren Tirabassi: A morning prayer for Ordinary Time.

+++

SONG: “Sólo le pido a Dios” (I Only Ask of God), performed by the Alma Sufí Ensamble: This is a cover of a 1978 song written in Spanish by the Argentine folk rock singer-songwriter León Gieco—a personal prayer that he would not be unfeeling, not numb to injustice. In a November 2023 collaboration with the Alma Sufí Ensamble, Gieco joined the Argentine Jewish cantor Gastón Saied (also a guest artist) and the ensemble’s own Nuri Nardelli, a practicing Sufi (Muslim mystic), in singing the song in Spanish, Hebrew, and Arabic, respectively. “Three languages, one heart. And one prayer for peace in the Middle East,” they write. View the original Spanish lyrics and English translation here.

+++

VIDEOS:

The following videos are two of thirteen—the ones focusing on the continent’s Christian heritage—from the docuseries Africa’s Cultural Landmarks, produced by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in collaboration with the World Monuments Fund and directed by Sosena Solomon. The series was commissioned to coincide with the reopening of the museum’s Arts of Africa galleries this May, after being closed for four years as part of a major redesign and renovation of the Michael C. Rockefeller Wing.

>> “Rock-Hewn Churches of Lalibela, Ethiopia”: “Stepping into one of the rock-hewn churches of Lalibela is an experience unlike any other. Carved directly from volcanic rock, from the top to bottom, unlike traditional buildings built from the ground up, the eleven wondrous churches of Lalibela are monumental expressions of devotion and symbols of Ethiopia’s spiritual heartland. Visually captivating and rich with personal insights from priests entrusted with care of the churches, this documentary reveals how these sanctuaries—both magnificent and fragile—face the constant threat of erosion. Meet the dedicated guardians balancing conservation and sacred duty, to ensure Lalibela’s living pilgrimage tradition thrives for generations to come.”

>> “Rock-Hewn Churches of Tigray, Ethiopia”: “High in Ethiopia’s Northern Highlands, the rock-hewn churches of Tigray stand as breathtaking sanctuaries of faith carved into sandstone cliffs. For centuries, some 120 rock-hewn churches, and the paintings and artifacts preserved within their walls, were protected by their remote locations. However, during the 2020–2022 war in Tigray, some churches were targeted, and the use of heavy weapons resulted in vibrations that caused cracks in the stone. Through evocative imagery and intimate testimonies, this documentary explores the endurance of these remarkable sites of devotion, as local priests reflect on the spiritual and cultural legacies at risk.”

+++

ESSAY: “Shaped for People: Sacred Harp Singing in the Age of AI” by Mary Margaret Alvarado: From Image journal’s summer 2025 issue: “What is that, I thought, when I first heard shape note singing. It was groaning, and some voices keened. It was loud. It was muscular, this music. There was glory, but it was not pretty. The voices did not blend, and the sound was not nice. All I knew was that I wanted to hear it again. Maybe it seemed to me like an aesthetic that does not lie? I feel surrounded, often, by aesthetics that do lie. . . . So there’s a contrarian appeal to a song that sounds sung by humans in their (young, old, crooked, fat, gorgeous, hairy, halt, jacked, sexy, bald, injured, hale) human bodies . . .”

Writer Mary Margaret Alvarado reflects on her experiences participating in shape-note hymn sings, a democratic form of communal music making using the “sacred harp” of the human voice. She provides an abridged history of such singing, which developed in late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century New England but is now carried on throughout the US and in the UK and Germany. I’d love to take part in a shape-note hymn sing someday, as I’ve long been drawn to the sound and tradition, which I know only from recordings. Besides the small gatherings organized by local communities, there are also large conventions, and I’ve been intrigued to learn that, despite the hymns’ deep rootedness in Christianity, non-Christians are often among the attendees.

Below are a few of the hymns Alvarado mentions in her essay: “Youth like the Spring Will Soon Be Gone” (MORNING SUN), “David’s Lamentation” over the death of his son Absalom, and “I’m Not Ashamed of Jesus” (CORINTH). Traditionally, the singers start by singing through an entire verse using only the four syllables of the Sacred Harp notation system (fa, sol, la, mi) as their lyrics, to orient themselves to the tune.

To browse previous Art & Theology posts that have featured hymns from the Sacred Harp tradition—albeit not all performed in a traditional manner; several are arranged for soloists or otherwise stylistically adapted—see https://artandtheology.org/tag/sacred-harp/.

+++

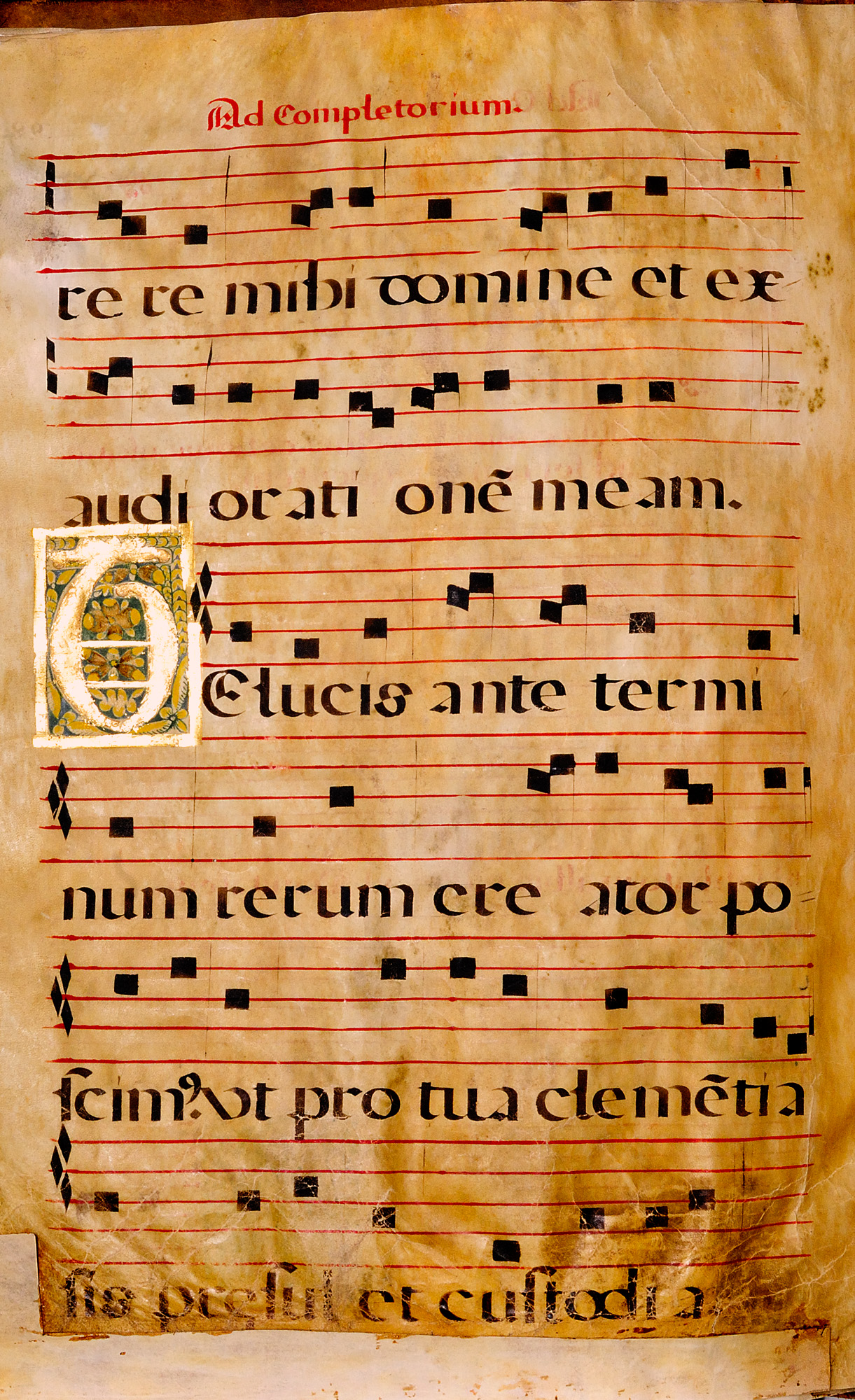

NEW ALBUM: Radiant Dawn by the Gesualdo Six: Released August 1 by the British vocal ensemble the Gesualdo Six, this album features “an ethereal combination of trumpet and voices to explore different shades of light . . . from the soft, golden glow of a summer evening as shadows lengthen to the shimmering of moonlight on calm waters,” writes director Owain Park. “Some texts contrast the terror of darkness with the brilliance of dazzling sunlight; others explore the blurred boundaries between heaven and earth. Plainchant threads this programme together . . .” A range of composers are represented, from the Middle Ages to the present day.

Several of the songs are based on biblical episodes—Simeon’s response to having held the Christ child in the temple, the transfiguration of Christ on Mount Tabor, the arrival of the holy women at Jesus’s tomb on Easter morning, the walk to Emmaus—or passages such as Psalm 5:2 (“O hearken thou . . .”) and Revelation 21:23 (“And the city had no need of the sun . . .”). There are bedtime prayers, a meditation on the glory of the angels, an O Antiphon for the approach of Christmas, and settings of contemporary poems, like “Grandmother Moon” by the Mi’kmaq poet Mary Louise Martin and “Aura” by Emily Berry, about the death of her mother. View the track list at https://www.hyperion-records.co.uk/dc.asp?dc=D_CDA68465.

Below, from the album, is the Gesualdo Six’s performance of “Night Prayer” by Alec Roth, a setting of the Te lucis ante terminum, featuring Matilda Lloyd on trumpet. “The stark setting reminds me of the ravages of war,” one YouTube user remarks. “The singing, of a prayer sent out over the carnage, blessing those who have suffered. Sacred space indeed.”