This is the third installment of my annual “25 Poems for Christmas” series. Included too, on the front end, are poems for Advent, the four-week season of preparation, hope, and expectation leading up to Christmas.

[Read volume 1] [Read volume 2]

1. “Advent (III)” by W. H. Auden, from For the Time Being: Voiced by the Chorus, who cry out from “a dreadful wood / Of conscious evil,” this is the third section of part 1 of Auden’s book-length Christmas poem in nine parts, For the Time Being—“the only direct treatment of sacred subjects I shall ever attempt,” he said. He wrote the poem in 1941–42. He had originally conceived it as the libretto of an oratorio that Benjamin Britten would write the music for, but the text turned out to be too complex, and Britten abandoned the project. The final two lines of this section set us up for the seemingly impossible feat of divine incarnation: “Nothing can save us that is possible: / We who must die demand a miracle.”

Source: For the Time Being: A Christmas Oratorio (Princeton University Press, 2013)

2. “Advent” by Robert Alan Rife: Ten sensory metaphors for Advent, conveying its mood of anticipation.

Source: https://innerwoven.me/ (author’s website)

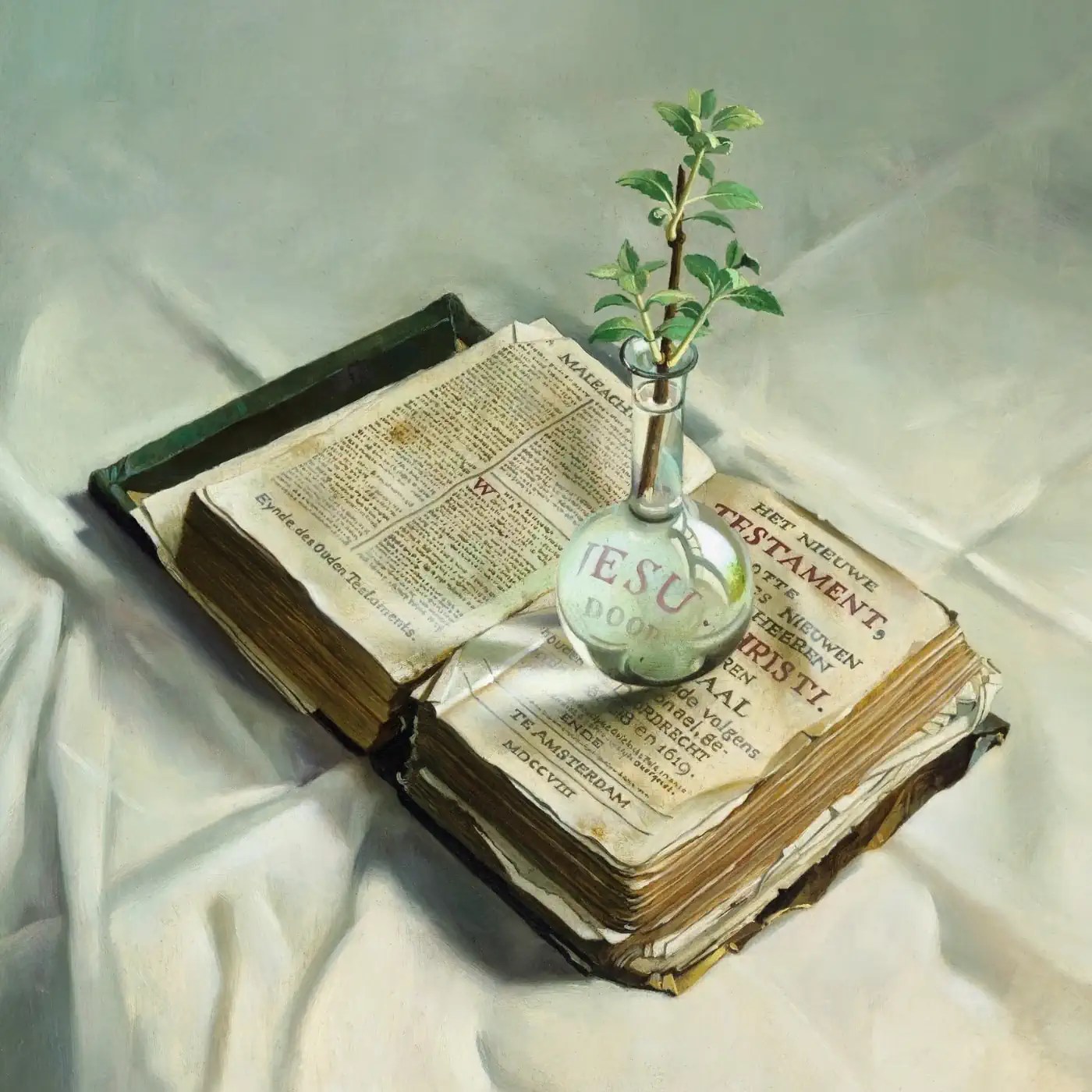

3. “O Orient Light” by James Ryman: Loosely influenced by the O Antiphons (a set of short chants used in medieval Advent liturgies), this Middle English lyric is by the fifteenth-century Franciscan friar James Ryman of Canterbury; it’s one of 166 sacred poems he published in a 1492 collection. Each stanza consists of one rhyme repeated six times, and the Latin refrain translates to “O Christ, king of the nations, / O life of the living.” The fourth stanza is a standout, connecting the salvation wrought by Christ to the healing properties of plants: “O Jesse root, most sweet and sote, / In rind and root most full of bote, / To us be bote, bound hand and foot, / O vita viventium.”

Source: Cambridge University Library, MS Ee. 1.12; compiled in The Early English Carols, ed. Richard Leighton Greene, 2nd ed., revised and enlarged (The Clarendon Press, 1977). Public Domain.

4. “Merger Poem” by Judy Chicago: “Merger Poem” is an aspiration that artist Judy Chicago wrote to accompany her 1979 monumental artwork The Dinner Party, a celebration of the richness of women’s heritage, expressed as place settings around a table, that is housed at the Brooklyn Museum. Her vision in the poem is not theistic, at least not explicitly so, but she uses the language of “Eden,” and her descriptions evoke passages from Isaiah about a future harmony, a merging of heaven and earth, in which justice and equity are achieved at last—not to mention the strong eschatological tones that feasting has in Christianity. Each line begins with “And then,” cumulatively generating a longing in the reader for “then” to arrive.

Source: The Dinner Party, exh. cat. (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1979) | https://judychicago.com/

5. “truth” by Gwendolyn Brooks: “And if sun comes / How shall we greet him?” the speaker asks at the opening of this poem. The sun here represents truth, revelation, illumination, which we may seek with weeping and prayer but which can be dreadful when it actually comes. It’s often more comfortable to stay asleep in the dark than to confront the stark brightness of day. But oh, what we miss when we do! Gwendolyn Brooks uses the pronoun “him” for the sun, and it’s easy to read the poem Christologically: you can read it in the sense of any of Christ’s three comings—as a baby in Bethlehem, in personal, inner ways (he reveals himself, and seeks entrance, to human hearts), or as a king and judge at the end of time. Did you catch the reference to Revelation 3:20?

Source: Annie Allen (Harper & Row, 1949); compiled in Blacks (Third World Press, 1987)

6. “Advent” by Mary Jo Salter: In this poem a mother and daughter are building a gingerbread house when a wintry gust tears a shutter on their actual house off its hinges, the shock of the thud causing, inside, a gingerbread wall to split. I think “house,” here, could be a metaphor for a faith structure; a house of belief. Shutters are doing a lot of work in the text: one falls off in a storm, and the daughter’s Advent calendar consists of twenty-five shutters, one opened each day until Christmas to reveal a Bible verse or narrative scene.

I’m not quite sure how to interpret the poem overall, but it seems to be addressing themes of (in)stability, brokenness and repair, the desire to believe versus the impulse to shut out belief, openness (“The house cannot be closed”), (dis)enchantment, the mother-child bond, and safety and danger (the Christmas story, like faith itself, characterized by both). I can’t decide if the “blank” in the final tercet sounds hopeful or bleak: does it connote possibility or lack? And is the mother suggesting in the final line (a repurposing of the final line from stanza 15) that what’s most real to her is not Mary and the baby Jesus but herself and her own child, right there in that moment?—or is she finding a point of kinship with Mother Mary in the love she feels for her offspring?

Source: Open Shutters (Knopf, 2003)

7. “Nativity” by Li-Young Lee: “What is the world?” asks a little boy in the darkness; and again as an adult. A poem of spiritual questing, Li-Young Lee’s “Nativity” deals with existential questions, ending with a tercet that evokes Isaac Watts’s famous carol line “Let every heart prepare him room.” Within us we must make a manger, a “safe place,” to receive the wild God.

Source: Book of My Nights (BOA Editions, 2001)

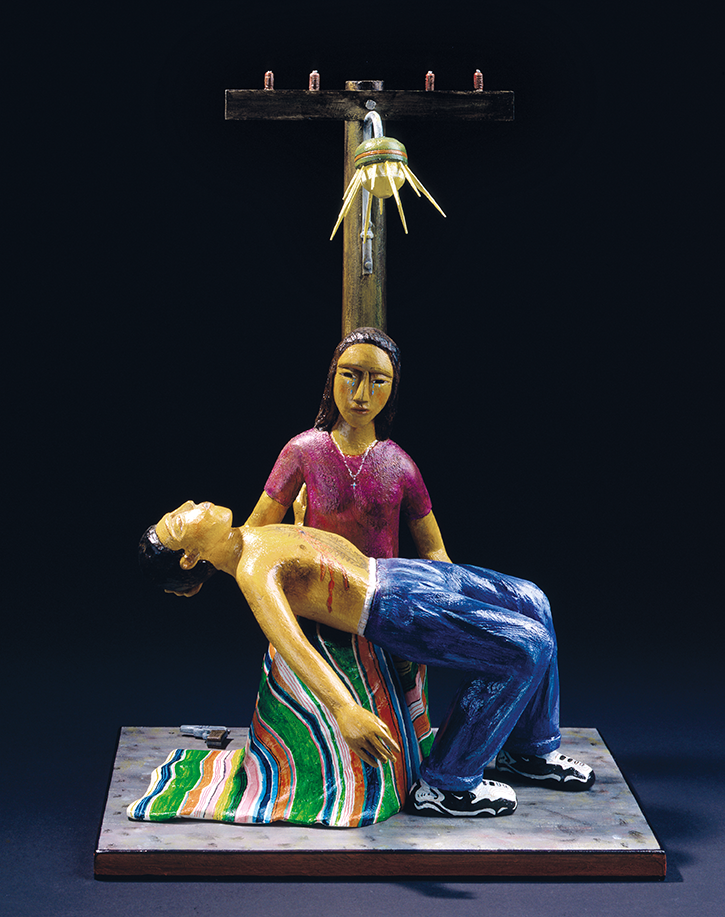

8. “Nazareth” by Drew Jackson: Ancient Nazareth, where Jesus grew up, was an insignificant village that many believed no good could come out of (see John 1:46). This poem by public theologian Drew Jackson accentuates Jesus’s origins there, his identity as a “southsider” (Nazareth is in southern Galilee). Today some urban neighborhoods on the “South Side” are disparaged, their residents dismissed as poor and lacking education and potential. God chose to incarnate in a rural neighborhood with a similar reputation, not simply dropping in and then leaving but, as the second person of the Trinity, being formed and nurtured in that environment. “Nazareth” is from Jackson’s debut poetry collection, in which he works his way through the first eight chapters of Luke’s Gospel, drawing out the theme of liberation and making contemporary connections.

Source: God Speaks Through Wombs: Poems on God’s Unexpected Coming (InterVarsity, 2021) | https://drewejackson.com/

9. “The Visitation” by Calvin B. LeCompte Jr.: The poet imagines the fields that Mary passes on her way to her cousin Elizabeth’s house joining in the Magnificat, praising the Savior in her womb.

Source: I Sing of a Maiden: The Mary Book of Verse, ed. Sister M. Thérèse (Macmillan, 1947)

10. “My Darling” by Alexandra Barylski: Mary and Joseph are cuddling in bed as she reflects on the divine interventions that brought and kept them together. The poem references the legend, originating in the second-century Protoevangelium of James and repeated in the seventh-century Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew, that Joseph was chosen to wed Mary when from his staff, submitted to the high priest along with those of other single men, there miraculously emerged a dove. Mary expresses appreciation for Joseph’s “visionary love,” patience, and courage in their relationship, his spiritual leadership and support.

Source: Reformed Journal, May 11, 2021

11. “A Blessing for the New Baby” by Luci Shaw: The speakers of this poem give a lovely benediction over Christ—preincarnate and then embryonic in the first stanza, then out of the womb in the second and third.

Source: Accompanied by Angels: Poems of the Incarnation (Eerdmans, 2006) | https://lucishaw.com/

12. “Love’s Delights” by Meister Eckhart, rendered by Jon M. Sweeney and Mark S. Burrows: The medieval German mystic Meister Eckhart didn’t write poetry, but many of his sermons have a poetic quality to them, so contemporary poet Mark S. Burrows and writer Jon M. Sweeney, working from an English translation of the Middle High German by Frank Tobin, reworked select excerpts into verse. Adapted from a sermon Meister Eckhart preached on Isaiah 60:1, this poem meditates on the downward movement of love that raises up.

Source: Jon M. Sweeney and Mark S. Burrows, Meister Eckhart’s Book of the Heart: Meditations for the Restless Soul (Hampton Roads, 2017)

13. “Word Become Flesh” by Seth Wieck: Pregnancy, childbirth, and nursing take a toll on the body. Voiced by Mary, this poem highlights the bodily realities of Jesus’s first coming—Mary swollen, bruised, cracked, and bleeding. She was wounded for our transgressions, in the sense that she endured kicks to the ribs, postpartum hemorrhoids, etc., in order to bring forth our Savior, and by these wounds, because they gave life to Jesus, our healing was made possible. The last sentence is a zinger. Mary gives (physical) birth to Jesus, and he gives (spiritual) birth to her.

Source: Fathom, December 21, 2017 | https://www.sethwieck.com/

14. “Prince of Peace” by Brian Volck: The poet provides his own introduction to this poem on his website: “Octavian Augustus, first emperor of Rome, was known by many titles, including Divi Filius (Son of God) and Princeps Pacis (Prince of Peace). An inscription in Asia Minor states that Augustus’s birth ‘has been for the whole world the beginning of the gospel (εύαγγέλιον) concerning him.’ How strange, then, to use the same names for a contemporaneous but obscure Palestinian Jew, whose understanding of peace, politics, and power was so radically different. How strange to have so long diluted the scandal of the gospel (good news) with accommodations to an Augustan vision of a peace built on the use or threat of lethal violence. Here’s a Christmas poem calling attention to that contrast in a conscious act against forgetting.”

Source: Flesh Becomes Word (Dos Madres, 2013) | https://brianvolck.com/

15. “The Burning Babe” by Robert Southwell: Consisting of sixteen lines in iambic heptameter, this poem by the Jesuit martyr-saint Robert Southwell [previously] relates a mystical vision of the Christ child, who appears to the narrator on a cold winter’s night, enflamed and hovering in midair. The poem develops the metaphor of the love of Christ as a fiery furnace that both warms and purifies.

Source: St Peter’s Complaint, and Other Poems (London, 1595). Public Domain.

16. “Advent 1966” by Denise Levertov: This poem is shocking in its horror. Written in 1966, it picks up Southwell’s image of the Burning Babe and transposes it to the napalmed villages of Vietnam, where children were being physically (not symbolically or ethereally, as in Southwell’s poem) set on fire by chemical weapons deployed by the US military. Denise Levertov [previously], who was an antiwar activist as well as a poet, uses repetition to strong effect, conveying a sense of the seemingly relentless carnage (the war produced an estimated two million civilian casualties, more than half the total number). Though addressing a specific historical event, this elegy for the innocent provokes us to consider where similar atrocities are happening today.

Source: To Stay Alive (New Directions, 1971); compiled in Making Peace, ed. Peggy Rosenthal (New Directions, 2006)

17. “Christmas Eve” by Christina Rossetti: The Victorian poet Christina Rossetti [previously] opens this lyric with two paradoxes that characterize Christmas—bright darkness and chilly warmth—referencing the general mood of cheer and comfort that coexists with the bleak English midwinter. Why this mirth? Because “Christmas bringeth Jesus, / Brought for us so low.” Jesus was brought down from heaven in the Incarnation, but he would be brought lower still: his spirits sunken in Gethsemane, his body buried in a grave. The second stanza evokes a wedding: dressed in a bridal gown of gauzy snow, earth receives her heavenly Bridegroom.

Source: Time Flies: A Reading Diary (London, 1885); compiled in The Complete Poems (Penguin, 2001). Public Domain.

18. “Hill Christmas” by R. S. Thomas: In a poor rural Welsh village, parishioners make their way across snowy fields, weather-beaten, on Christmas to feed their bodies and souls with a snow-white bread loaf and crimson wine. In the celebration of the Eucharist, they hear love cry “in their heart’s manger.” Then they return to the day’s chores. I think the last line refers to a wayside crucifix.

Source: Laboratories of the Spirit (Macmillan, 1975); compiled in Collected Poems, 1945–1990 (Dent, 1993)

19. “back in the day” by Carl Winderl: In a practice known as “setting lambs on,” when a baby lamb dies in birth, sheep farmers will often take a live lamb (an orphan, or a twin or triplet from another ewe) and cover it in the skin of the deceased one so that, when the grieving mother smells the familiar scent of her deceased offspring, she accepts the lamb as her own. In Carl Winderl’s poem, Mother Mary reflects on that practice and has a premonition of a dead lamb.

Source: Christian Century, December 27, 2023

20. “Hymn 4 on the Nativity of Christ” by Ephrem the Syrian: St. Ephrem, a church father from the fourth century, wrote his theology in verse and is one of the most significant Early Christian hymnists. His Nativity hymns are my favorite; I’m particularly struck in Hymn IV by his meditation on how the Christ who suckles at Mary’s breast also gives suck to the whole world. “He is the Living Breast of living breath,” as Kathleen E. McVey translates the Syriac.

Source: Ephrem the Syrian: Hymns, trans. Kathleen E. McVey (Classics of Western Spirituality) (Paulist Press, 1989)

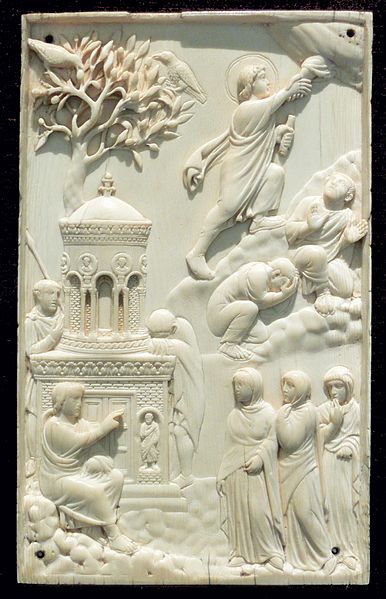

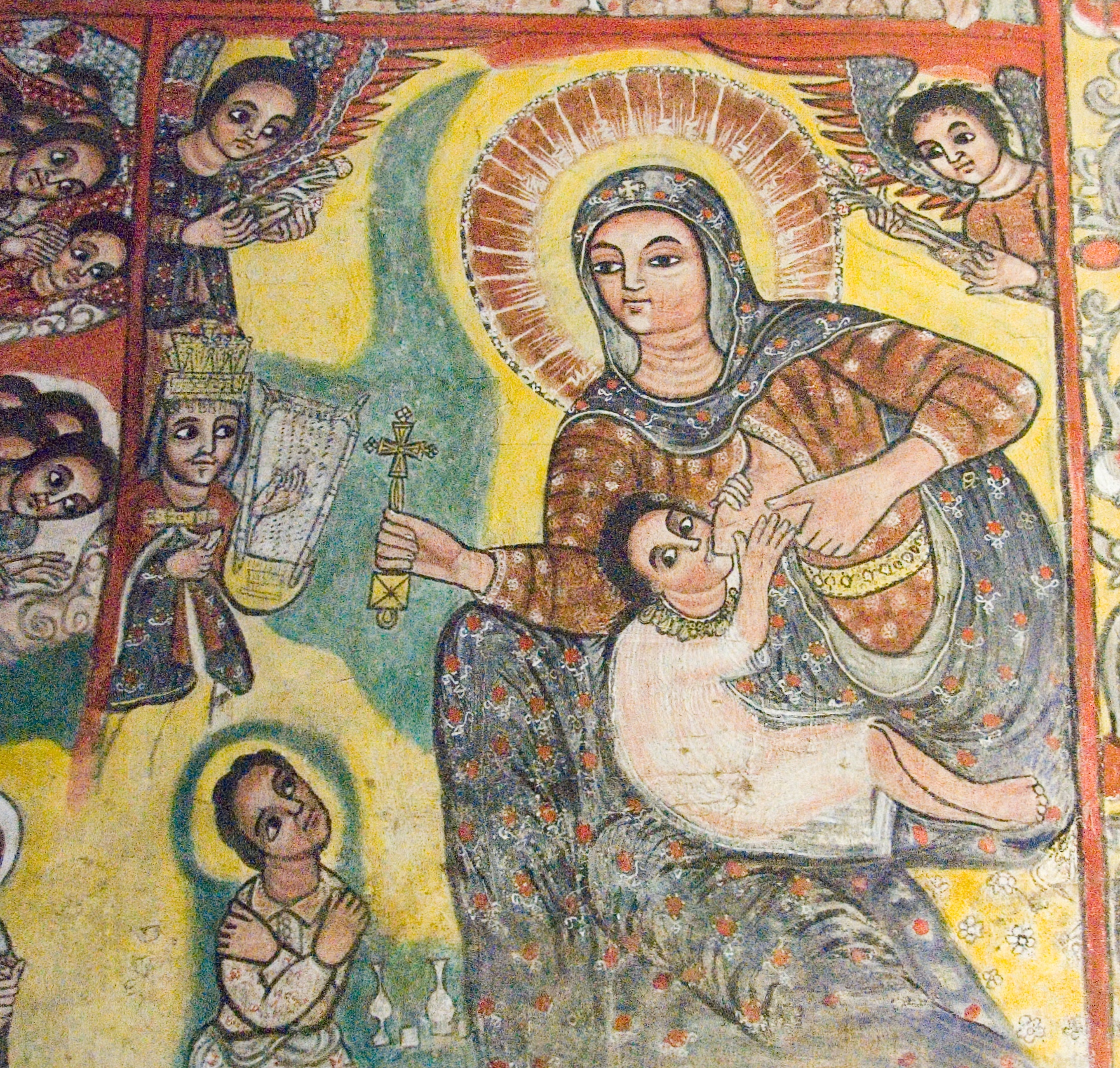

21. “Nativity” by Scott Cairns: This is the first in a pair of ekphrastic poems called “Two Icons,” in which the poet, who is Greek Orthodox, describes an icon from his home prayer corner. The first three stanzas engage in constructive wordplay: Jesus is wrapped in swaddling bands by his mother, and she is rapt—enraptured, wholly absorbed—by him. She holds him in her gaze and in her hands, and is beholden to him. Icons are about just that: beholding Christ and the sacred mysteries and deepening our affection for the One who holds us in affection. In Nativity icons our gaze is directed to “the core / where all the journeys meet, appalling crux and hallowed cave and womb,” where we are beckoned, like the magi, to bow before the incarnate God.

Source: Compass of Affection: Poems New and Selected (Paraclete, 2006)

22. “Star of the Nativity” by Joseph Brodsky: The Nobel Prize–winning Russian poet Joseph Brodsky was born into a Jewish family, but he was captivated by the story of Jesus’s birth and wrote many poems about it. The final stanza of this one gives us the unique perspective of the Star of Bethlehem, looking down—the Father’s beaming pride.

Source: Nativity Poems (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2001)

23. “Wise Women Also Came” by Jan Richardson: The Gospel of Matthew tells us that when Jesus was born, wise men came from the east to worship him. But wise women came too, Jan Richardson surmises. They came during Mary’s labor—midwives assisting with the birth. They came with lamps, fresh water, and blankets.

Source: Night Visions (Wanton Gospeller, 2010)

24. “Green River Christmas” by John Shea: Theologian and storyteller John Shea reflects on how, after experiencing something scary or unpleasant (like getting a shot or a teeth cleaning), mothers often give their child a treat. Christmas is a kind of supreme treat after the penitential season of Advent, during which we confronted the state of our spiritual health and remedied any shortfalls. Think, too, of the liturgy of (somber) confession and (sweet) pardon every Sunday at church, a prelude to the feast of bread and wine. At the Lord’s Table, we are fed—the gifts of God for the people of God. The Eucharist is the subtext of the final stanza, where Shea describes the presentation of Jesus in the temple forty days after his birth. There he is received by “the long-starved arms / of Simeon and Anna.” They had hungered for salvation, endured a long period of waiting; now they are filled.

Source: Seeing Haloes: Christmas Poems to Open the Heart (Liturgical Press, 2017)

25. “Taking Down the Tree” by Jane Kenyon: “Tick, tick, the desiccated needles drop.” This poem is about the passing of time—the death of another year—and the glumness that often sets in after the holidays are over, but it’s also about the storage of memories. In many households, Christmas ornaments are a multigenerational collection of memories. As with hanging them on the tree, taking them off and packing them away is a ritual that may prompt us to revisit certain past experiences or periods in our life. After we unplug the stringed lights and wrap up the baubles for safekeeping, then what? How will we inhabit the twelve months until next Christmas?

Source: Collected Poems (Graywolf, 2005)