Last summer my husband and I drove up to Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, to see the Joseph Stella: Visionary Nature exhibition at the Brandywine Museum of Art, which ran June 17–September 24, 2023. (Before that it was shown at the Norton Museum of Art in West Palm Beach, Florida, and the High Museum of Art in Atlanta.) It was lovely! There’s an accompanying catalog still available.

Joseph Stella (1877–1946) was born in the mountain village of Muro Locano in southern Italy, near Naples, and immigrated to New York at age eighteen, becoming a US citizen in 1923. He traveled much throughout his life—between his native country and his adopted country, but also for extended stays in Morocco, Chad, Algeria, France, and Barbados. In Paris in 1911–12 he met many of the leading artists of the European avant-garde, including Matisse, Picasso, and Modigliani, and was exposed to the full range of developments in modern art—postimpressionism, Symbolism, fauvism, cubism, surrealism, futurism, dadaism.

Though Stella absorbed some of these influences, he never aligned with a single group or movement. Art historian Abram Lerner says Stella is difficult to pin down, describing him as “a multiple stylist of unusual scope and energy,” both a modernist and a traditionalist. [1] In terms of content, his oeuvre is divided fairly evenly between urban industrial subjects—his most famous paintings are probably those from his series on the Brooklyn Bridge—and joyful and abundant nature.

Joseph Stella: Visionary Nature, curated by Stephanie Heydt and Audrey Lewis, spotlights the latter. Many of Stella’s paintings feature birds and foliage hieratically positioned around a central axis, such as Dance of Spring (Song of the Birds).

“Here,” reads the wall text,

Stella assembles a classical temple of flora and fauna—in his own words, culled “from the elysian lyricism of the Italian spring.” Flowers rise from a pink lotus at the base of a central column, culminating in the curious combination of lupine and a longhorn steer’s head flower, a floral form that resembles a bull’s skull. Below perch three sparrows, the national bird of Italy and a favorite of Stella’s.

At over six square feet, Stella’s Flowers, Italy is an even more epic floral composition, a symphony of vitality and color.

From the wall text:

Order and symmetry are in constant tension with the spontaneity of organic ornamentation. The canvas overflows with colorful depictions of flowers and birds within a setting evoking Gothic architecture: pillars of gnarled tree trunks extend outward from the center, as if aisles of a cathedral. Lupine, gladiolas, and birds-of-paradise fill the vertical spaces with a spectrum of colors simulating stained glass windows. Like a congregation in the pews, a host of smaller flowers and plants are gathered below.

Despite the title, the flowers depicted are not all native to Italy; Stella culled them from his world travels, and some are his own mystical inventions.

Stella sought to portray the voluptuousness and spirituality of his Italian homeland. He was raised in the Catholic faith, and although he didn’t practice as an adult, he remained proud of that heritage. Devotion to the Virgin Mary was a prominent aspect of his religious experience growing up, and in the 1920s he began painting a series of Madonnas, three of which were part of this exhibition.

Art historian Barbara Haskell identifies some of the artistic influences on these paintings:

The garlands of fruits and flowers that surrounded his Madonnas and their embroidered garments of lacy floral patterns recalled the work of the fifteenth-century Venetian Carlo Crivelli, while their impassive countenances, downcast eyes, and long, slim hands folded under translucent cloaks owed a debt to the Dugento masters Cimabue and Duccio. Yet Stella’s paintings were equally influenced by the flat, naive, and colorful images of the Madonna that proliferated in the popular devotional images and folk art of Southern Italy . . . in prayer sheets and books, scapulars, and ex-votos as well as in the profusion of silk and plastic flowers on altars and religious images. [2]

His 1926 Virgin from Brooklyn Museum is my favorite. It shows Mary enshrined among the fruits and flowers of the Mediterranean, with tendrils sweeping up and down her mantle and robe, adorning her neck like a necklace, sprouting out of her prayerful hands, and encircling the womb where she gestated Jesus. The Joseph Stella: Visionary Nature curators provided the following commentary in the wall text:

Eyes downcast and hands folded in a traditional Christian gesture of spiritual humility, Stella’s Madonna is set against the distinctive topography of Naples. Visible in the background is Mount Vesuvius, the smoldering volcano that erupted in AD 79 and a landmark of Southern Italy. The halo-like orb surrounding the Virgin’s head, seemingly nestled into the profiles of the mountains, transforms the modern Naples into a site of religiosity. Stella described “the Virgin praying [. . .] protected, on both sides, by almond blossoms, crowned above by the wreath of the deep and clear gold of the orange and lemon trees.”

Stella captures the wild beauty, the fecundity, the blossoming of Mary when the Holy Spirit plants his seed in her and she conceives God’s Word. Her acceptance of the divine call that the angel Gabriel relays to her produces life that redounds to all of humanity and indeed to the whole world. It’s why Mary’s cousin Elizabeth exclaims to her, “Blessed are you among women, and blessed is the fruit of your womb!” (Luke 1:42).

There’s a long tradition in Christianity of describing Mary’s conception of Jesus as a flowering and of honoring her with flowers. I’m reminded especially of the twelfth-century mystic Hildegard of Bingen’s many hymns and antiphons that celebrate Mary in such terms.

Yes your flesh held joy like the grass

when the dew falls, when heaven

freshens its green: O mother

of gladness, verdure of spring. [3]

Pierced by the light of God,

Mary Virgin,

drenched in the speech of God,

your body bloomed,

swelling with the breath of God. [4]

You glowing,

most green,

verdant sprout,in the movement of the spirit,

in the midst of wise and holy seekers,

you bud forth into light.Your time to blossom has come.

Balsam scented,

in you

the beautiful flower

blossomed. [5]

The Brooklyn Virgin could be read as an Annunciation image, the Incarnation taking place inside this young woman who said yes to God. The sailboats on the sea, their movement reliant on the wind, may allude to the Holy Spirit who blew onto the scene in a major way in Luke 1 to move salvation history forward.

The reference to outdoor religious processions with painted wooden Madonnas in southern Italy is more pronounced in Stella’s Purissima, in which the Mary figure, nearly life-size, is very stiff, statuesque. Co-curator Stephanie Heydt from the High Museum of Art introduces the work in this three-and-a-half-minute video:

“Mater Purissima” (Purest Mother), or “Virgo Purissima” (Purest Virgin), is one of Mary’s titles in Catholicism. The artist gave the following description of the painting:

Clear morning chanting of Spring.

BLUE intense cobalt of the sky—deep ultramarine of the Neapolitan sea, calm and clear as crystal—and alternating with zones of lighter blue, the mantle multicolored (an enormous lily blossom turned upside down).

SILVER quicksilver of spring water, quilted with the rose, green, and yellow of the gown—greenish silver, very bright—mystic DAWN-white—of the Halo.

WHITE as snow for the two herons, whose gleaming white necks enclose, like a sacred shrine, the prayer of the VIRGIN.

YELLOW very light—for the edges of the mantle—to bring it out clearly with diamond purity, and reveal the hard firm modeling of the virginal breast. The lines of the mantle fall straight over the long hieratic folds of the gown, forming a frame—and the full, resonant yellow of unpeeled lemons at both sides of the painting like echoing notes of the propitious shrill laughter of SPRING.

VIOLET mixed with ultramarine for the zigzag motif in the panel along the edge of the mantle, and bright, fiery violet at the top of Vesuvius, near the white fountainhead of incense—light violet tinged with rose, for the distant Smile of Divine Capri.

GREEN soft, tender, like the new grass—intense green for the short pointed leaves that enclose the lemons—and a dark green, both sour and sweet, for the palms that fan out at the sides like mystic garlands.

PINK strong—rising to the flaming, pure vermilion borders—of the Rose, brilliant as a jewel, in contrast to the waxy pallor of the hands clasped in prayer—and infinitely subtle, delicately modulated rose for the small flowers that with the others of various colors weave of dreams and promises and splendid bridal gown of the “Purissima.” [6]

Like his Brooklyn Virgin, this painting is also set in the Bay of Naples, with Mount Vesuvius gently erupting in the right background, and the island of Capri rising up out of the sea on the left.

Three pink lilies create a frame around the Purissima, their long stalks rising up on either side of her, with one flower bending down to crown her head with its filaments and anthers. She is attended not by angels but by herons, along with other critters at her feet. This is a Madonna both earthy and supernal.

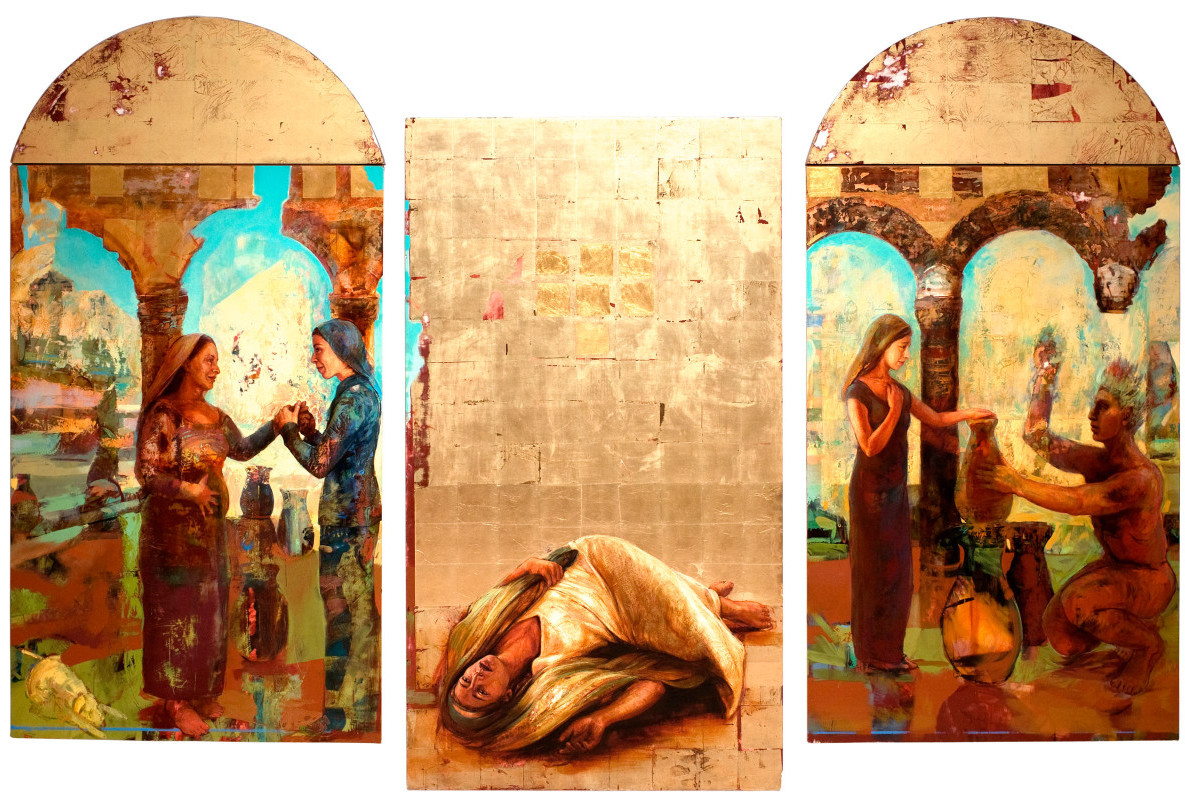

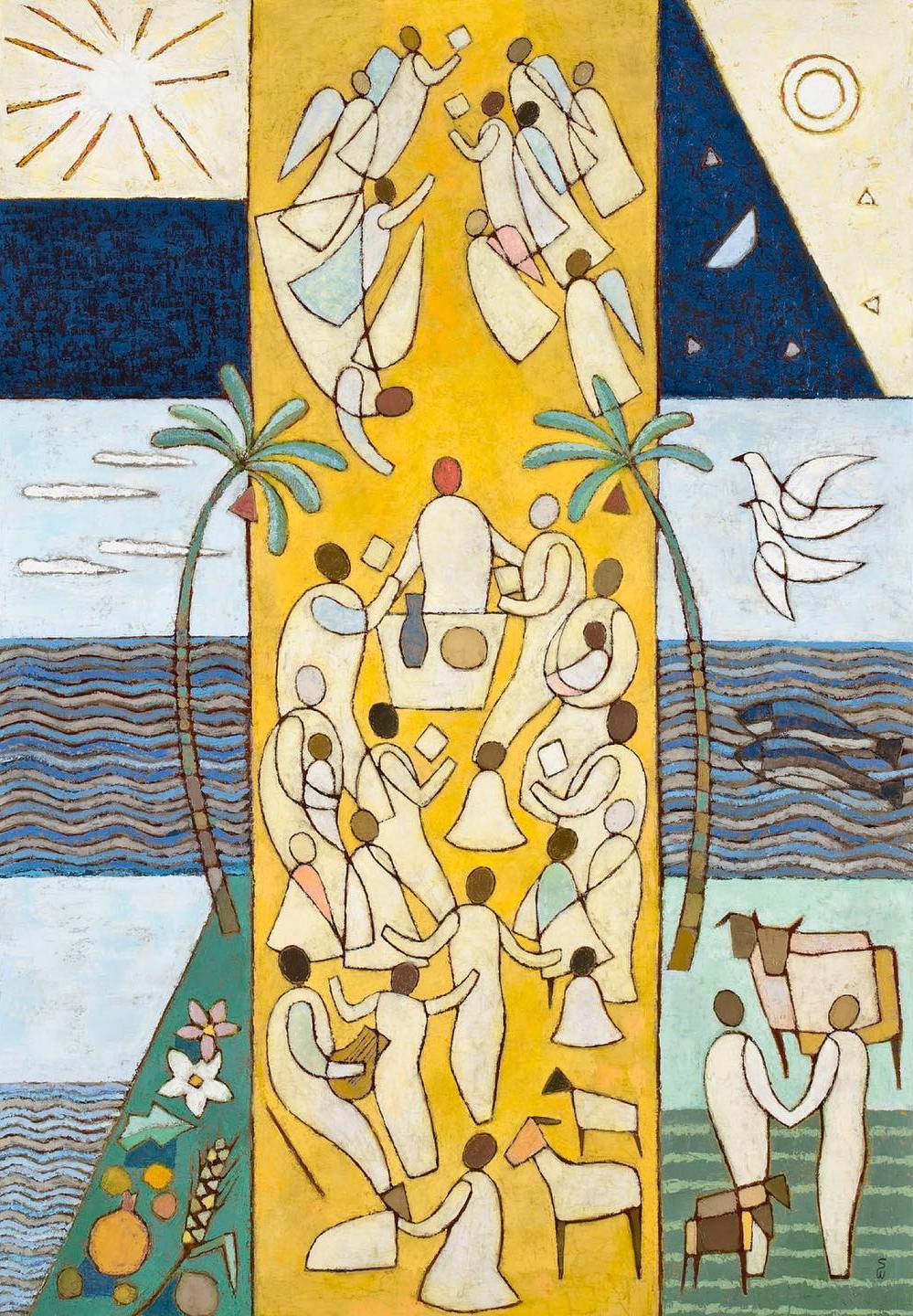

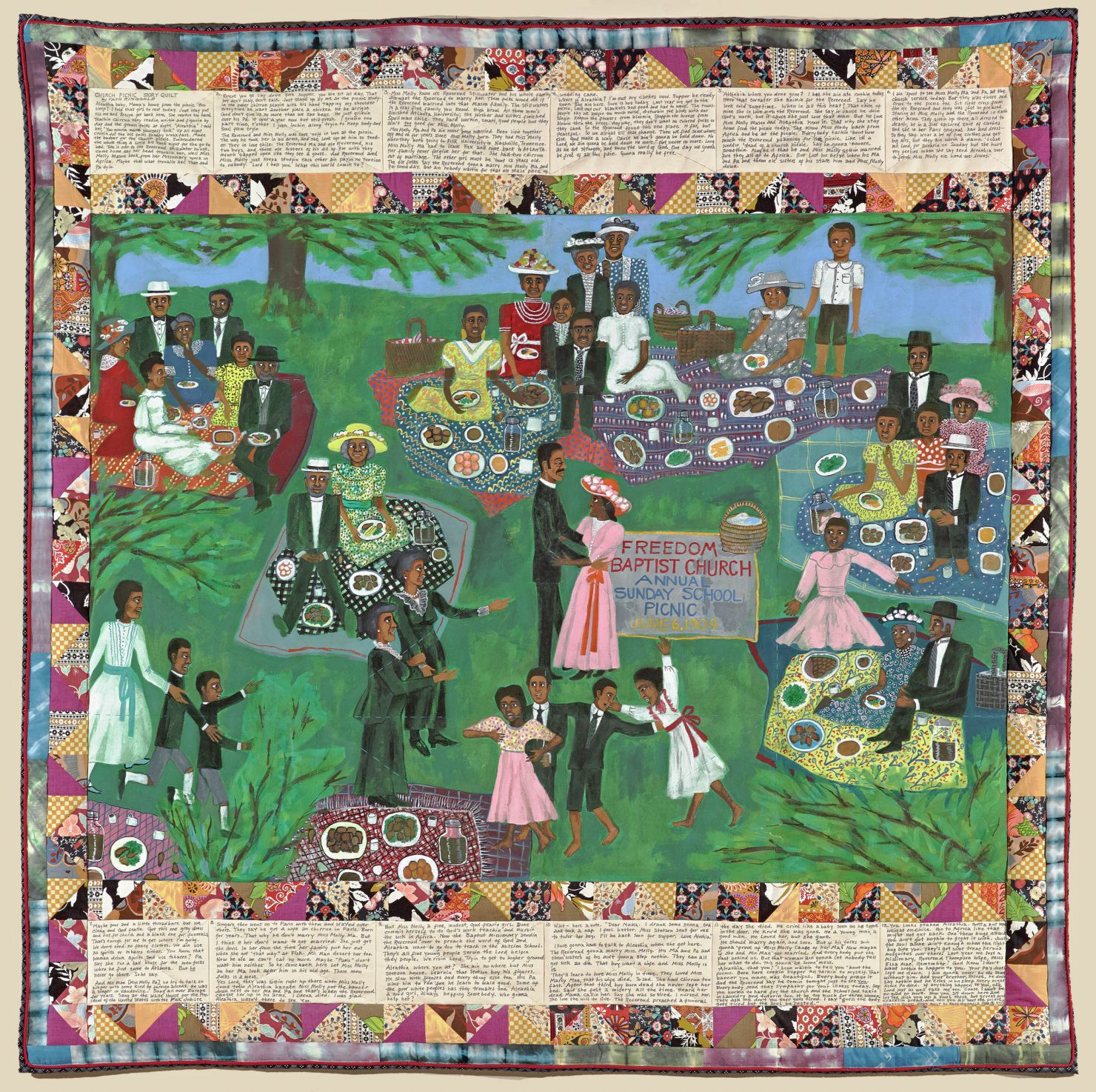

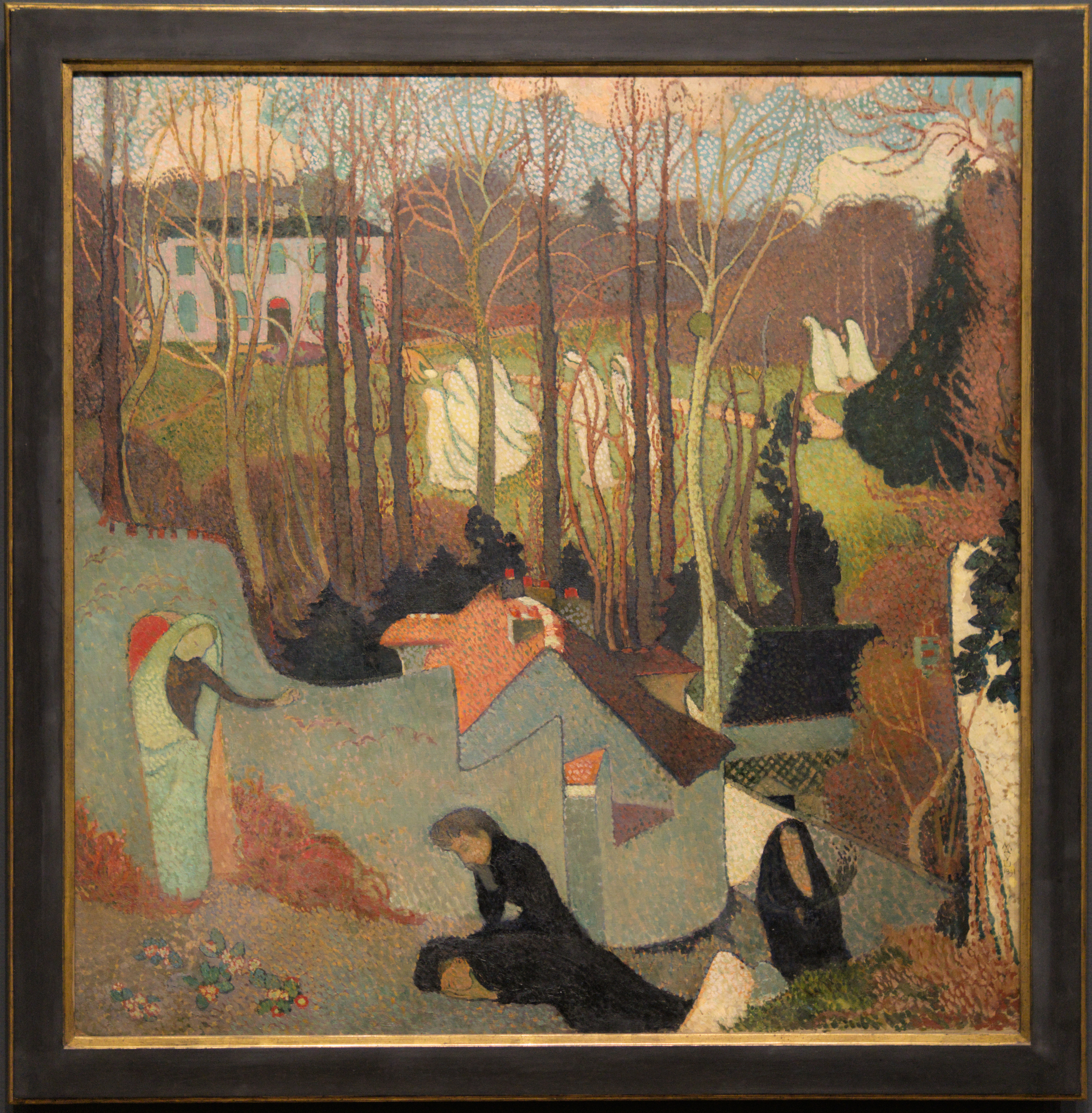

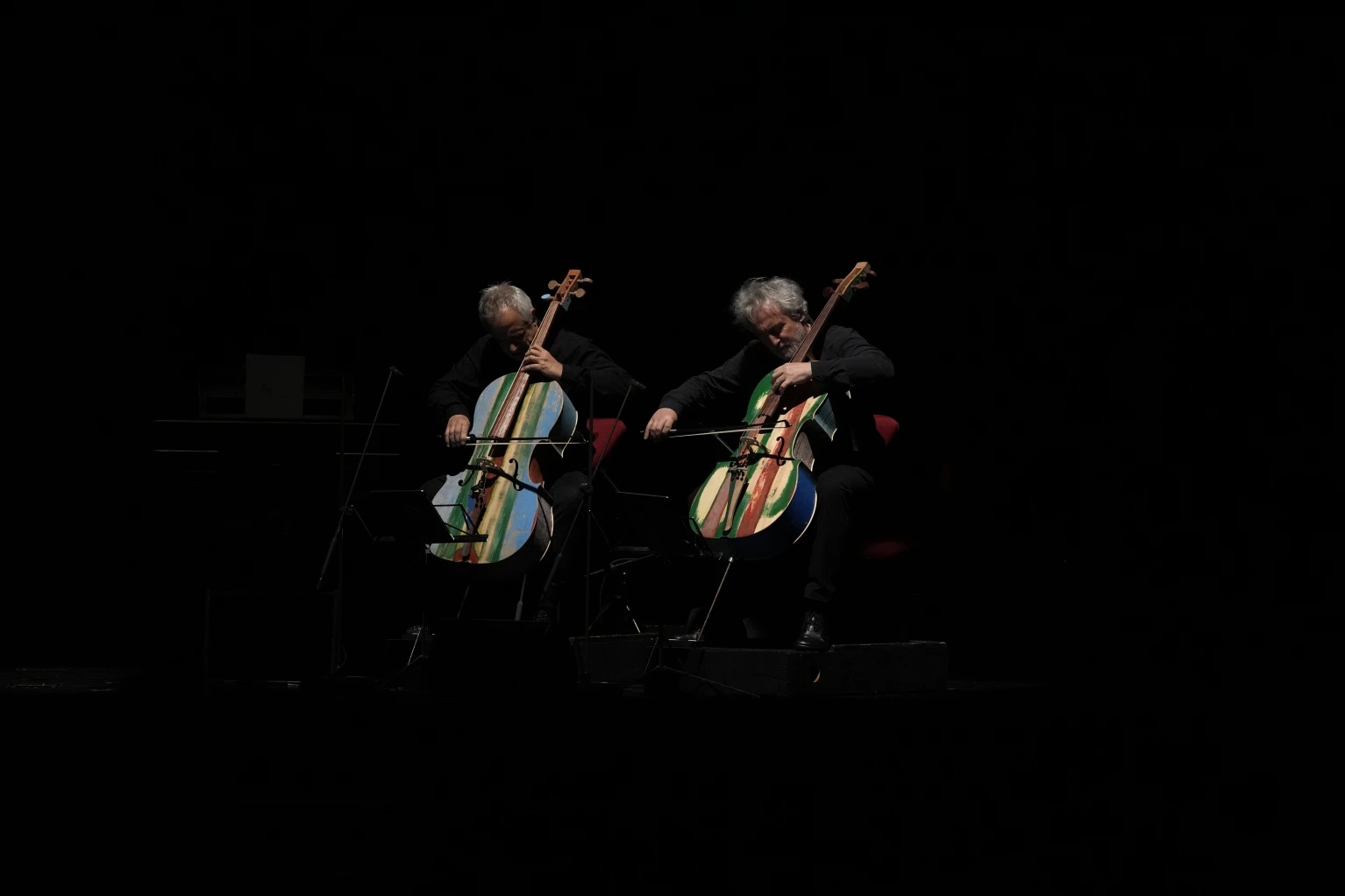

Here are a few more photos from the exhibition:

View additional select images in the exhibition’s press kit.

NOTES

1. Abram Lerner, foreword to Judith Zilczer, Joseph Stella: The Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden Collection (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1983), 6.

2. Barbara Haskell, Joseph Stella (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art / Harry N. Abrams, 1994), 151.

3. From Hildegard of Bingen, “Hymn to the Virgin,” trans. Barbara Newman, in Symphonia: A Critical Edition of the “Symphonia armonie celestium revelationum” (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1988, 1998), 123.

4. From Hildegard of Bingen, “Antiphon for the Virgin,” in Symphonia, 137.

5. From Hildegard of Bingen, “A Song to Mary,” rendered by Gabriele Uhlein, in Meditations with Hildegard of Bingen (Rochester, VT: Bear & Co., 1983), 119.

6. English translation from Irma B. Jaffe, Joseph Stella (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1970), 99–100. For the original Italian, see appendix 1, #29.