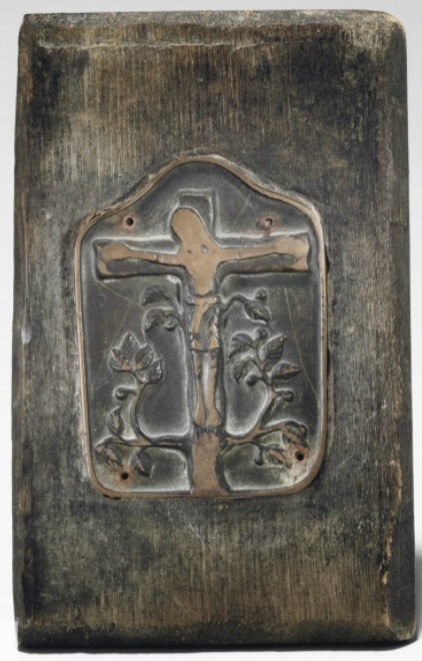

I first learned about fumi-e (“stepping-on pictures”) while reading about the history of Christian art in Japan. These objects are bronze likenesses of Jesus, sometimes shown together with his mother, Mary, that the religious authorities of the Tokugawa shogunate of Japan required suspected Christians to step on in order to prove that they were not members of that outlawed religion. If the apprehended persons refused, they were tortured and, if that didn’t break them, killed—most notoriously, by being boiled to death in the volcanic springs of Mount Unzen.

This period of persecution lasted from 1629 to 1858.

Fumi-e factor heavily into Shūsaku Endō’s 1966 historical novel Chinmoku (Silence), which tells the story of two Jesuit missionaries who travel to Japan in 1639 to find their missing mentor—rumored to have apostatized—and to continue the work he started there with the underground church. Written by Endō partly in response to the discrimination he experienced as a Japanese Catholic, the novel is about the struggle for faith in a world marked by God’s seeming absence. It received the highly esteemed Tanizaki Prize the year of its release and instantly became a best seller; it was translated into English in 1969.

Since then it has been the basis of several artistic adaptations: a stage play, also by Endō; a Japanese film by Masahiro Shinoda; a Portuguese film by João Mário Grilo; an opera by Teizo Matsumura; a symphony by James MacMillan—and now an American film by Martin Scorsese, the same director who brought us Raging Bull, The Last Temptation of Christ, The Departed, and The Wolf of Wall Street. He dedicates it “to Japanese Christians and their pastors.”

Twenty-eight years in the making, Scorsese’s “passion project,” Silence, has been lauded as “one of the best films ever made about Christian faith.” The Telegraph calls it a “plangent, scalding work of religious art . . . soul-pricklingly attuned to matters transcendent and eternal.” Time Out says it “ranks among the greatest achievements of spiritually minded cinema.” “An anguished masterwork of spiritual inquiry,” the Los Angeles Times declares, that “ponders the dogmas, riddles and anxieties of Christian faith with a rigor and seriousness that . . . has few recent equivalents in world cinema. . . . A work of insistent, altogether confounding grace.” Eric Metaxas says, “This may be the most Christian film I have ever seen—and that includes The Passion.”

Released in theaters December 23, 2016, Silence stars Andrew Garfield as lead character Father Sebastião Rodrigues, and Adam Driver as his compatriot, Father Francisco Garrpe. Liam Neeson plays the apostate Cristóvão Ferreira. See the trailer below.

Before I found out Scorsese was adapting Endō’s Silence, I learned of the novel from visual artist Makoto Fujimura, whose own work and theology have been very much influenced by it. Last May he published the book Silence and Beauty: Hidden Faith Born of Suffering, about his journey with Endō through art, trauma, and cultural heritage.

“Endō is a novelist of pain but not of despair,” Fujimura says. “He’s a novelist of compassion.” (Scorsese, who consulted with Fujimura on the film, echoes this assessment in an interview: “In Endō, tenderness and compassion are always there. Always. Even when the characters don’t know that tenderness and compassion are there, we do.”) The central (external) conflict of the book, and film, is the proposition the Inquisitor gives Father Rodrigues: he can either step on the fumi-e, or else witness the torture and death of the young Christians under his charge. What should he do?

Fujimura sees the fumi-e as the truest, most enduring image of Christ, because it speaks so much of Christ’s condescension and grace, his coming to us to be trampled. While many Christians went to their deaths during the Edo persecutions, others chose the fraught path of publicly renouncing their faith with the stomp of their foot while secretly retaining it, in hiddenness. Fujimura notes how Endō is the spiritual child of those who stepped on fumi-e, and marvels how the story of a severely oppressed religious minority was thrust out of hiding with the publication of Silence, garnering special acclaim in the very country whose government perpetrated those acts of oppression (and whose population is less than 1 percent Catholic!), and how the voices of those once forced into silence are now being projected from Hollywood. It’s all God’s grace, Fujimura says.

Prior to the film’s release, Macmillan issued a new edition of Silence as part of its Picador Modern Classics imprint. Along with it they released a compilation of reflections on the novel by forty-five Christians from different denominational affiliations, among them Os Guinness and Philip Yancey, as well as a discussion guide.

I appreciate how Christian universities have been preparing their students to receive the major motion picture and increasing engagement with the literary source text. Wheaton College chose Endō’s Silence as a core text of its new Christ at the Core curriculum for freshmen and mounted an exhibition of associated artifacts, with responsive paintings by Fujimura. (I commend the prayer card Wheaton provides to guide viewers through the exhibition space, encouraging a spiritual experience, not simply information intake.)

Fuller Theological Seminary hosted an on-campus screening and brought Scorsese in to speak to attendees about faith and film; a Catholic and a former seminarian, he says he likes to explore the ambiguities, the contradictions, of faith, while remaining rooted in it.

Calvin College’s Institute of Christian Worship hosted a discussion on “Silence, Beauty, and the Shape of Christian Discipleship,” in which Fujimura, philosopher Nicholas Wolterstorff, and theologian Neal Plantinga share their encounters with the novel.

Overall, Christians have had a very positive reaction to Scorsese’s film (though inevitably, those who prefer movies from the “faith-based” genre do not like its ambiguity, which is present in the novel too). I want to highlight two glowing reviews from mainstream media: one from Vox, and one from the Los Angeles Times—both written by Christians.

In “Silence is beautiful, unsettling, and one of the finest religious movies ever made,” Alissa Wilkinson identifies the theme of religious hubris:

The genius of Endō’s story and Scorsese’s adaptation is that it won’t characterize anyone as a saint, nor will it either fully condone or reject the colonialist impulses, the religious oppression, the apostasy, or the faltering faith of its characters. There is space within the story for every broken attempt to fix the world. Endō’s answer still lies in Christ, but his perception of Christ is radically different from what most people are familiar with. . . .

In Silence, nobody is Christ but Christ himself. Everyone else is a Peter or a Judas, a faltering rejecter, for whom there may be hope anyway. What Scorsese has accomplished in adapting Endō’s novel is a close reminder that the path to redemption lies through suffering, and that it may not be I who must save the world so much as I am the one who needs saving.

Justin Chang, writing for the Los Angeles Times, also picks up on the film’s emphasis on humility and grace:

Endō’s novel wrecked me when I read it three years ago, for both its consolation and its challenge. It struck me then as both a wrenching affirmation of a savior’s unfathomable grace and a thorough dismantling of everything that Christianity has often aligned itself with across the centuries: the arrogant pursuit of its own power and authority, and a willingness to do harm in the name of one who stood for unconditional mercy. Scorsese’s film continues that dismantling, brilliantly and unsparingly.

Chang concludes his review with a triad of searing questions prompted by the film.

In response to Silence’s Oscar snubs (it’s nominated only, but well deservedly, for Rodrigo Prieto’s cinematography), Chang wrote a second article expressing the ways in which it is superior to Mel Gibson’s six-time-nominated Hacksaw Ridge, another English-language period drama starring Andrew Garfield as a Christian protagonist.

The films,

for all their superficial similarities, could scarcely be more different in dramatic tone, visual style and moral attitude. “Hacksaw Ridge” is a pulse-pounding, proudly unsubtle bloodbath that . . . allows its director to indulge his propensity for screen violence in the guise of a pacifist statement. . . . There is also, of course, a great deal of suffering on display in “Silence,” but while the film’s attitude toward its victims can feel alternately empathetic and distanced, it never once tilts into exploitation. Nor does it ever threaten to eclipse the film’s provocative ideas. . . .

Both “Hacksaw Ridge” and “Silence” aspire to the condition of religious art — to say something urgent and meaningful about what it means to be a follower of Christ in a hostile and divided world. . . . But while “Silence” takes faith seriously enough to treat it as the devilish, all-consuming paradox it is, “Hacksaw Ridge” backs it as a sure thing.

Furthermore, Garfield’s character arc is far more complex in Silence, his performance more demanding.

Silence may not have been adequately recognized by the Academy, but it has garnered a lot of critical praise, as I’ve already shown. Even nonreligious viewers have been compelled by it. In Time magazine’s review, you can hear critic Stephanie Zacharek’s surprise:

It’s a little strange to think of a film that’s ostensibly about Christianity as one that casts a spell. But . . . when Scorsese shows us a group of peasants apostatizing—one by one, they’re led up to a metal plate imprinted with an image of Jesus and exhorted to stomp on it—the sight of their muddy sandaled feet, sullying the sacred, induces a kind of trance like horror.

“Gorgeous, haunting,” she writes on top of that. A “radiant exploration of what it means to believe in the grace of God.”

Emma Green’s review in The Atlantic is titled “Martin Scorsese’s Radical Act of Turning Theology Into Art.” The deck reads, “Rarely do mainstream films treat religious questions with seriousness and specificity. Silence, a movie about 17th-century Jesuit missionaries, shows what that can look like.” Green says Scorsese’s film is unique among religious-themed dramas because “it’s actually art”—not only in that the production is high-quality, but in that it engages with ambiguity. Unlike those from the “faith-based” genre, which treat faith as a simple point to be made and exist to affirm the worldview of their viewers, this film aims to challenge, to “deepen people’s understanding of themselves and the world.”

It is the textured portrayal of Christian faith that attracted Scorsese to the novel in the first place. In his foreword to Picador’s 2016 edition of Silence, he writes,

How do you tell the story of Christian faith? The difficulty, the crisis, of believing? How do you describe the struggle? . . .

On the face of it, believing and questioning are antithetical. Yet I believe that they go hand in hand. One nourishes the other. Questioning may lead to great loneliness, but if it coexists with faith—true faith, abiding faith—it can end in the most joyful sense of communion. It’s this painful, paradoxical passage—from certainty to doubt to loneliness to communion—that Endō understands so well, and renders so clearly, carefully and beautifully in Silence.

In preparation for his role as a Jesuit priest, Garfield studied with Father James Martin for a year, learning Jesuit history, theology, and spirituality, which included (at Garfield’s initiative) fasting, celibacy, and the Ignatian Spiritual Exercises. The Exercises are a compilation of meditations, prayers, and contemplative practices developed by the order’s founder, in which the practitioner is invited to imaginatively place himself into various scenes from the life of Jesus, so as to be drawn into a deeper relationship with him. Garfield—who notes the Ignatian influence on Stanislavski’s development of method acting—took to the Exercises like a duck to water.

The Jesuit magazine America published an excellent interview with Garfield, where he opens up about how the Exercises “changed me and transformed me, . . . showed me who I was,” and, quite unexpectedly, led him to fall in love with Jesus. Interviewer Brendan Busse, SJ, writes,

When I asked what stood out in the Exercises, he fixed his eyes vaguely on a point in the near distance, wandering off into a place of memory. Then, as if the question had brought him back into the experience itself, he smiled widely and said: “What was really easy was falling in love with this person, was falling in love with Jesus Christ. That was the most surprising thing.”

He fell silent at the thought of it, clearly moved to emotion. He clutched his chest, just below the sternum, somewhere between his gut and his heart, and what he said next came out through bursts of laughter: “God! That was the most remarkable thing—falling in love, and how easy it was to fall in love with Jesus.”

You have to read the whole piece. Garfield talks about “the beauty of living a hidden life, of retreating”; how imagining himself at the Nativity filled him with an overwhelming desire to be of service; and how making Silence was “deeper than any other artistic experience I’ve ever had,” but that deeper still was his journey through the Exercises.

This isn’t empty talk he dishes out only to Christian media outlets because they eat it up; you can hear his authenticity in the Late Show interview he did last month with Stephen Colbert:

Scorsese has done several interviews about the film as well. Here’s one conducted by America magazine:

Also worth checking out is the print interview by Jeffrey Overstreet.

Excellent analysis! I read another review on the film Silence a couple of days ago where the reviewer recommended it as a soulful challenge as one ponders on contemporary issues locally and globally. I immediately pre-ordered the DVD.

LikeLike

[…] killed. Confronted with a terrible dilemma they must choose: recant their faith by stepping on a fumi-e and set the Japanese Christians free, or hold onto their faith and let others suffer. It is an […]

LikeLike

[…] I heard Your voice,” he says. Besides hearing the voice of Christ asking him to trample on the fumi-e, he recognizes that G-d was all around him, even if not speaking directly to him in his prayer. G-d […]

LikeLike