LOOK: Chr. Geb. by Jörg Länger

The contemporary German artist Jörg Länger creates extraordinary mixed-media works, many of which are in dialogue with Christian art history. In addition to earning an advanced degree in art, Länger has also done university coursework in theology and philosophy, so it’s no wonder his pieces demonstrate a keen theological awareness and spiritual sensibility.

After some fifteen years of working in photography, installation art, performance art, and conceptual art, in 1998 Länger shifted gears to focus on drawing, painting, and printmaking. He developed a series, still ongoing, that he calls “Protagonisten aus 23.000 Jahren Kulturgeschichte” (Protagonists from 23,000 Years of Cultural History), in which he takes figures from prehistoric petroglyphs and bas-reliefs, ancient Greek vases, medieval manuscripts, European Renaissance paintings, and contemporary art, simplifies them, and puts them into a new pictorial context. He copies the figure’s outline onto a linoleum block, inks and prints it to produce a sort of silhouette, and builds out from there using oil paint, pastels, wax, and/or gold leaf, while still retaining a minimalist aesthetic.

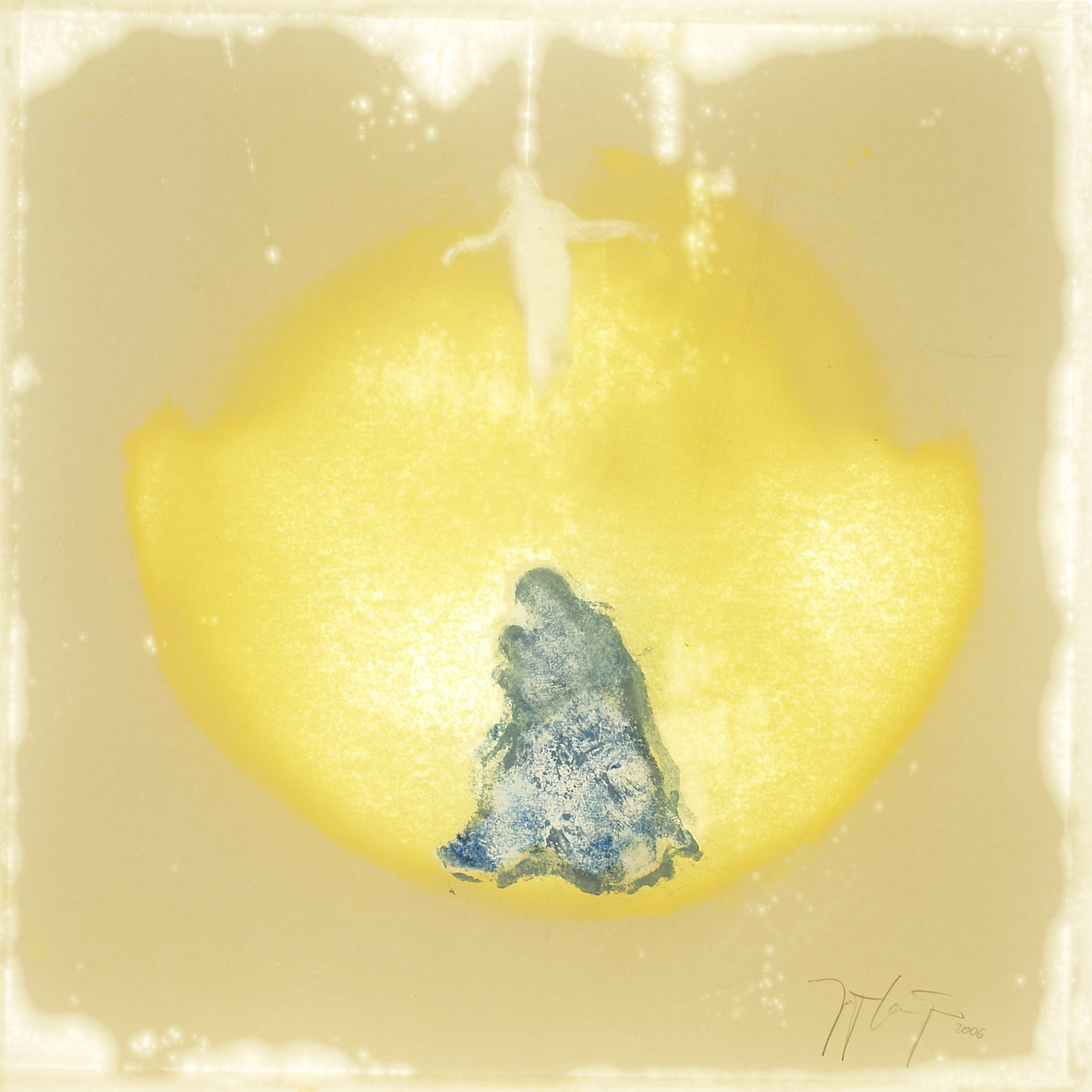

In his 2006 piece Chr. Geb. (short for Geburt Christi, “Birth of Christ”), the silhouetted figures are taken from Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece and Fra Angelico’s Entombment of Christ.

With the shadowy blue central pair of Mother and Child, the ghostly impression of Christ’s crucified body (being dragged into a tomb in the scene it’s excised from), the expanding puddle of gold that holds together both birth and death, and the light that presses in from the edges, the work has a mystical feel. It shows the Eternal One entering time, born of a woman, to live and die and rise and so bring humanity back to God and back to their truest selves.

LISTEN: “O Vis Aeternitatis” by Hildegard of Bingen, ca. 1140–60 | Performed by Azam Ali, 2020

V. O vis aeternitatis

que omnia ordinasti in corde tuo,

per Verbum tuum omnia creata sunt

sicut voluisti,

et ipsum Verbum tuum

induit carnem

in formatione illa

que educta est de Adam.

R. Et sic indumenta ipsius

a maximo dolore

abstersa sunt.

V. O quam magna est benignitas Salvatoris,

qui omnia liberavit

per incarnationem suam,

quam divinitas exspiravit

sine vinculo peccati.

R. Et sic indumenta ipsius

a maximo dolore

abstersa sunt.

V. Gloria Patri et Filio

et Spiritui sancto.

R. Et sic indumenta ipsius

a maximo dolore

abstersa sunt.

V. O power within Eternity:

All things you held in order in your heart,

and through your Word were all created

according to your will.

And then your very Word

was clothed within

that form of flesh

from Adam born.

R. And so his garments

were washed and cleansed

from greatest suffering.

V. How great the Savior’s goodness is!

For he has freed all things

by his own Incarnation,

which divinity breathed forth

unchained by any sin.

R. And so his garments

were washed and cleansed

by greatest suffering.

V. Glory be to the Father and to the Son

and to the Holy Spirit.

R. And so his garments

were washed and cleansed

by greatest suffering.

Trans. Nathaniel M. Campbell

Hildegard of Bingen [previously] was a twelfth-century German nun and polymath who wrote works on theology, medicine, and natural history; hymns, antiphons, and a drama for the liturgy (all with original music); and one of the largest bodies of letters to survive from the Middle Ages. In 1136 she was unanimously elected to lead her Benedictine community as abbess, which she did until her death in 1179.

“O vis aeternitatis” is the first entry in Hildegard’s Symphonia armonie celestium revelationum (Symphony of the Harmony of Celestial Revelations), a compilation of her liturgical songs that she made during her lifetime. It is labeled a “Responsory to the Creator.” “The responsory, one of several compositional forms Hildegard used,” explains medievalist Nathaniel M. Campbell, “is a series of solo verses [marked V] alternating with choral responses [marked R] sung at the first office of the day, vigils (matins), in the monastic liturgy.” It’s basically a call-and-response song.

This responsory, Campbell continues, “contemplate[s] the Incarnation . . . as the pivotal moment in which creation reached its perfect and predestined trajectory.” He notes how the refrain meditates on the cleansing of Adam’s flesh both from suffering and by (Christ’s) suffering. God put on our humanity and redeemed it.

Here’s how the medievalist Barbara Newman translates the responsory on page 99 of the critical edition of the Symphonia published by Cornell University Press:

Strength of the everlasting!

In your heart you invented

order.

Then you spoke the word and

all that you ordered

was,

just as you wished.And your word put on vestments

woven of flesh

cut from a woman

born of Adam

to bleach the agony out of his clothes.The Savior is grand and kind!

From the breath of God he took flesh

unfettered

(for sin was not in it)

to set everything free

and bleach the agony out of his clothes.Glorify the Father,

the Spirit, and the Son.He bleached the agony out of his clothes.

In the video above, “O vis aeternitatis” is performed by Azam Ali, an internationally acclaimed singer, producer, and composer who was born in Iran and raised in India and is now based in Los Angeles. She writes in the video’s YouTube description that Hildegard is part of the canon of universal spirituality and mysticism and that she is attracted to her cosmology, especially her articulation of the ancient philosophical concept of “the music of the spheres.”

In addition to her solo work, Ali is part of the musical group Niyaz, who blend medieval Sufi poetry and ancient Middle Eastern folk songs with modern electronic and trance music.