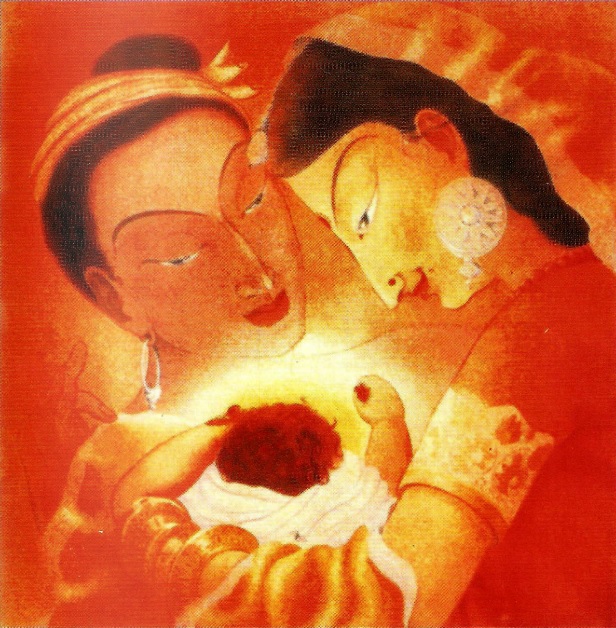

LOOK: The Passion of Mary by Katherine Kenny Bayly

This collage by Katherine Bayly is from the 2006 CIVA traveling exhibition Highly Favored: Contemporary Images of the Virgin Mary. In seven alternating vertical bands, it combines Michelangelo’s Pietà from St. Peter’s Basilica with a Virgin and Child painting by Laurent de La Hyre, showing Christ’s birth and death as two sides of the Incarnation coin. One can hear echoes of Simeon’s prophecy to Mary, that “a sword will pierce your own soul too” (Luke 2:35)—a veiled reference to the Crucifixion.

Since the Middle Ages artists have often embedded symbolic or other visual references to Christ’s passion in Nativity paintings—a goldfinch, a coral rosary, a bunch of grapes, a cave that recalls the tomb, swaddling bands that look like burial wrappings, a manger that looks like a sarcophagus or altar, or, more explicitly, angels holding the arma Christi (instruments of the passion). Sometimes artists would use a diptych format to juxtapose images of Mary holding Jesus as a vibrant young infant with her holding him as a pale adult corpse deposed from the cross, a pairing that strikes an emotional tenor, as there’s perhaps no deeper grief than a mother’s loss of a child. Bayly draws on this tradition in The Passion of Mary, foreshadowing a future sorrow and reminding us that Christ came to earth not only to live but also to die.

LISTEN: “Baby Boy” by Rhiannon Giddens, on Freedom Highway (2017)

Baby boy, baby boy, don’t you weep

Baby boy, baby boy, don’t you weep

You will be our savior

But until then, go to sleepYoung man, young man, I’ll watch over you

Young man, young man, I’ll watch over you

While you lead our people to the promised land

I will shelter youBaby boy (Young man)

Baby boy (Young man)

Don’t you weep (I will watch over you)

Baby boy (Young man)

Baby boy (Young man)

Don’t you weep (I will watch over you)

You will be (You will be)

Our savior

But until then, go to sleepBeloved, beloved, I will stand by you

Beloved, beloved, I will stand by you

When you leave this place to do what you must

I will always love youBaby boy (Young man) (Beloved)

Baby boy (Young man) (Beloved)

Don’t you weep (I will watch over you) (I will stand by you)

Baby boy (Young man) (Beloved)

Baby boy (Young man) (Beloved)

Don’t you weep (I will watch over you) (I will stand by you)

You will be (You will be)

Our savior

But until then, go to sleep

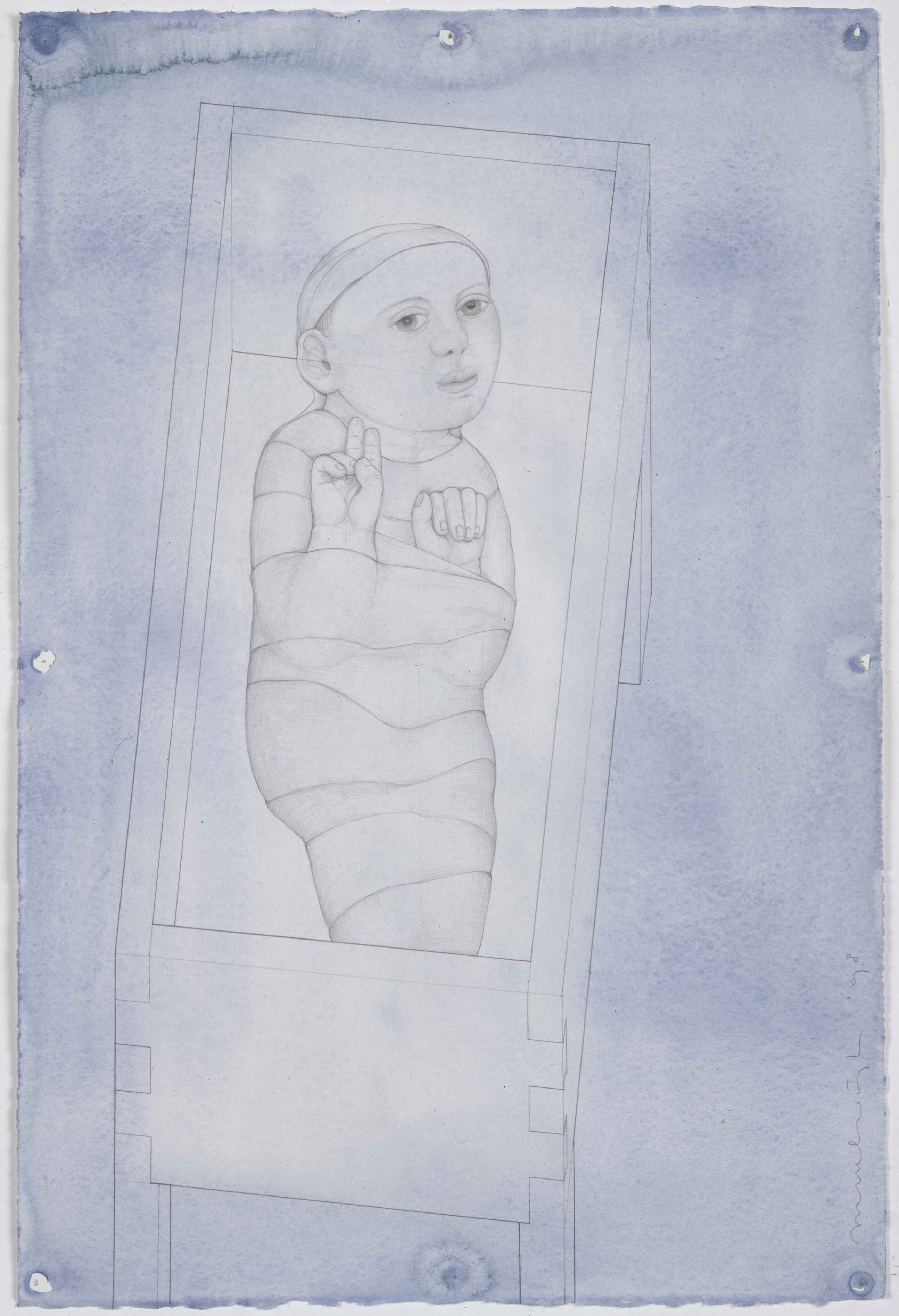

Poignantly performed by Rhiannon Giddens [previously], Lalenja Harrington, and Leyla McCalla, “Baby Boy” is a lullaby written in the voice of a mother to her son, her salvation, whom she sings to sleep. She pledges to always watch over, shelter, and support him to the best of her ability.

The subject of the song could be Moses and the speaker his birth mother, Jochebed, as there’s mention of him leading his people to the promised land. This boy will grow up to shepherd a nation into its rest.

Or it could be Jesus, the New Moses, who liberated humanity at large, breaking their bondage to the powers of evil. Remembering the angel’s promise, Mary whispers her grand hopes to this cuddly little bundle she holds who will be their fulfillment, even as she shushes his cries.

Note, though, how there are three voices singing—a trio of women, a sisterhood united in their love of this child and their eager expectation of deliverance. Think of the women who, against all odds, ensured Moses’s protection as a young one and those who later walked alongside him in his difficult calling. Think, too, of all the women who supported Christ throughout his ministry, materially and spiritually, standing by him until the end, mourning his death, and spreading the news of his resurrection. One might imagine this song being sung by the three Marys, for example. They have a faint sense of the danger ahead and know the hero Jesus will become, but for now, they simply wish him sound slumber and sweet dreams. “Until then . . .”