BLOG POST: “An open letter to pastors (A non-mom speaks about Mother’s Day)” by Amy Young: There’s disagreement among church leaders on whether Hallmark holidays, such as Mother’s Day, should be recognized during a worship service, and if so, how. Having mothers stand (while women who are not mothers in the conventional sense remain seated) can be very othering and bring up feelings of sadness or shame. It’s also a day when people are thinking about their own mothers, which can evoke a complex range of emotions.

Amy Young believes there is a way to honor mothers in church without alienating others, as well as to acknowledge the breadth of experiences associated with mothering. She has drafted a pastoral address that I find so wise and compassionate. Some women are estranged from their children. Some have experienced miscarriage or abortion. Some have had failed adoptions, or failed IVF treatments. Some placed a child for adoption. Some have been surrogate mothers. Some are foster mothers, or are the primary guardian of a relative’s child. Some are spiritual moms. Some women want to be mothers but have no partner or have had trouble conceiving. Some were abused by their mothers. Some have lost mothers. Some never met their mother. Young puts her arms around all these people who are potentially in the pews on Mother’s Day, making room for the complexity of the day—which does include celebration!

+++

VIDEO: “United with Beauty: The Psalms, the Arts, and the Human Experience” by Mallory Johnson: Mallory Johnson graduated last weekend with a bachelor’s in music and worship (concentration: voice) from Samford University in Birmingham, Alabama. (In the fall she will be starting an MDiv program at Beeson Divinity School.) All the seniors in the Samford School of the Arts are required to complete a capstone project tailored to their individual interests and career goals. As Johnson’s interests center on theology, history, and the arts, she created a twenty-minute video rooted in the Psalms that integrates music, poetry, short excerpts of fiction, visual art, and quotes from van Gogh, Tchaikovsky, Goethe, Luther, and others, resulting in a contemplative multimedia experience.

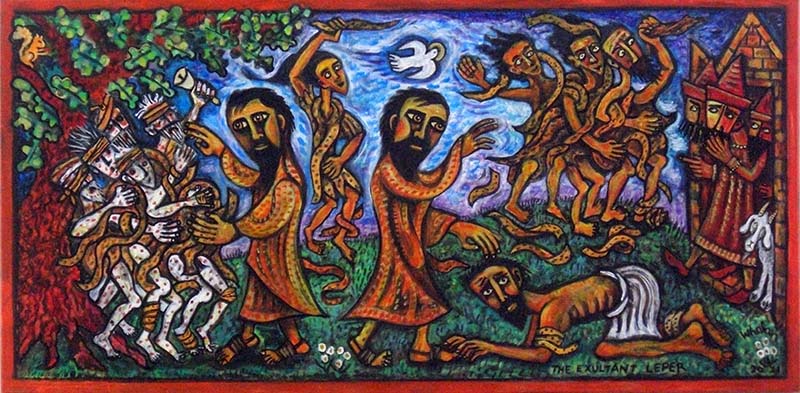

I resonate so much with Johnson’s approach of bringing together works from different artistic disciplines to interpret one another and to invite the viewer into worship. Her curation is stellar! To cite just one example, the contemporary choral work Stars by Ēriks Ešenvalds plays as we see, among other images, an Aboriginal dot painting of the constellations Orion and Canis and a nighttime landscape by realist painter Józef Chełmoński. Another: John Adams’s double piano composition “Hallelujah Junction” is brought into conversation with Psalm 150 and a painting by Jewish artist Richard Bee of David dancing before the ark.

The video opens with the theme of awe and wonder—expanses of sky and sea and field; the beauty and vastness of God mirrored in the natural world—and then moves to lament—of the prospering of the wicked; of exhaustion, anxiety, and other forms of mental or spiritual anguish and their causes; of personal sin—and finally ends with an assurance of grace and with exultation. Johnson shows how the longings of modern people overlap with those of the biblical psalmists. Here’s her description:

In his famous work titled Confessions, St. Augustine writes this: “Yet to praise you, God, is the desire of every human.” Is this true? What does this look like?

During my time at Samford, I have felt my heart and mind overflow with love for the arts. As a Christian, they have played a devotional role in my life. I find such joy in seeing connections between music, art, and literature that may seem unrelated on the surface. I believe that all humans have a longing for the goodness of God and we find “echoes” of Him everywhere, and most beautifully in artistic expression.

I wanted to show others how I understand the world as a Christian artist. This project is a journey through the Psalms, using art to reinforce the idea that the Psalms capture the full universal human experience. Across time and space, we have all felt the same things and we have all had the same deep longing for “something higher.”

I hope you can allow this project to wash over you. Make time to watch it alone or with someone you love, distraction-free. Turn the lights out, light a candle, watch it on a big screen with the volume up loud. Be cozy under a blanket with a cup of coffee, or grab a journal and write down anything that sticks out to you! It is my earnest desire that you will be moved by the artistic expression of humanity, and that you may realize that God has always been the goodness you most deeply desire.

+++

SONGS:

>> “Broken Healers” by Elise Massa: Singer-songwriter Elise Massa is the assistant director of music and worship arts at Church of the Ascension in Pittsburgh. A meditation on Christ as Wounded Healer, this song from her 2014 album of demos, We Are All Rough Drafts, was inspired by an Eastertide sermon.

Here’s the final stanza (the full lyrics are at the Bandcamp link):

Broken healers are we all

In a living world, decayed

With broken speech we stutter, “Glory”

As broken fingers mend what’s frayed

Holy Spirit, come, anoint us

As you anointed Christ the King

Who wore the crown of the oppressed

Who bears the scars of suffering

>> “Agnus Dei” by Michael W. Smith, performed by the Ukrainian Easter Choir: This is one of the few CCM songs I listened to as a young teen (Third Day’s version from a WOW CD!) that I’m still really fond of. In this video that premiered April 17, an eighty-person choir conducted by Sergiy Yakobchuk was assembled from multiple churches in Ukraine to perform for an Easter service in Lviv organized by the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association. Michael W. Smith’s “Agnus Dei” is one of three songs they sang, in both English and Ukrainian. The name of the soloist is not given. Many of the vocalists in the choir have been displaced from their homes by the current war with Russia. One of them says, “With the war, celebrating the Resurrection means for us now life above death, good above evil.”

+++

PRAYER EXERCISE: “Visio Divina: A 20-Minute Guided Prayer Reflection for the Crisis in Ukraine”: Visio divina, Latin for “divine seeing,” is a spiritual practice of engaging prayerfully with an image, usually an artwork—allowing the visual to invite you into communion with God. On March 17 Vivianne David led a virtual visio divina exercise with Natalya Rusetska’s Crucifixion, hosted by Renovaré. I caught up with the video afterward and found it a very meaningful experience. As the painting is by a Ukrainian artist and represents Christ’s passion, the war in Ukraine is a natural connection point.

I appreciate David’s wise guidance, which includes these reminders:

- Stay with the image, regardless of whether or not you “feel” something happening right away. There is something beautiful about faithfully waiting with that space, having dedicated it to God as a time of prayer.

- Notice what draws your attention, what invites you into the image—let that become a space for conversation with Christ.

- Notice what sort of emotions arise as you stay with the image. How does it awaken desire? Let these emotions lead you back to continued dialogue with God.

This kind of quiet, focused looking with an openness to encounter is something I encourage on the blog. Any of David’s three tips above I would also suggest for any art image I post—a corrective to hasty scrolling habits. Stick around for the last four minutes of the video to see dozens and dozens of impressions from participants, which may reveal new aspects of the painting to you.