This is part two of a three-part series based on some of my art encounters at the Christians in the Visual Arts conference held June 13–16, 2019, at Bethel University. This post covers a handful of notable artworks I was introduced to through slides; part three will cover art I experienced in person through the conference’s exhibitions and auction. Read part one, about the Sacred Spaces tour of Minneapolis, here.

In his introductory remarks to the 2019 CIVA conference, Chris Larson cited Lauren Bon’s Artists Need to Create on the Same Scale That Society Has the Capacity to Destroy, the eponymous work of the Brooklyn Rail–curated exhibition running through November 24 at the church of Santa Maria delle Penitenti in Venice, a collateral event of the Venice Biennale. It’s a great rallying quote, one that I hadn’t heard before but that I can really get behind.

The theme of the conference was “Are We There Yet,” a deliberately broad question which I took as referring to the conversation between serious art and serious faith, which CIVA has been heavily engaged in over its forty-year history. We talked about where “there” is and unpacked other aspects of the conference title, but I’m sidestepping those discussions to focus on the visual.

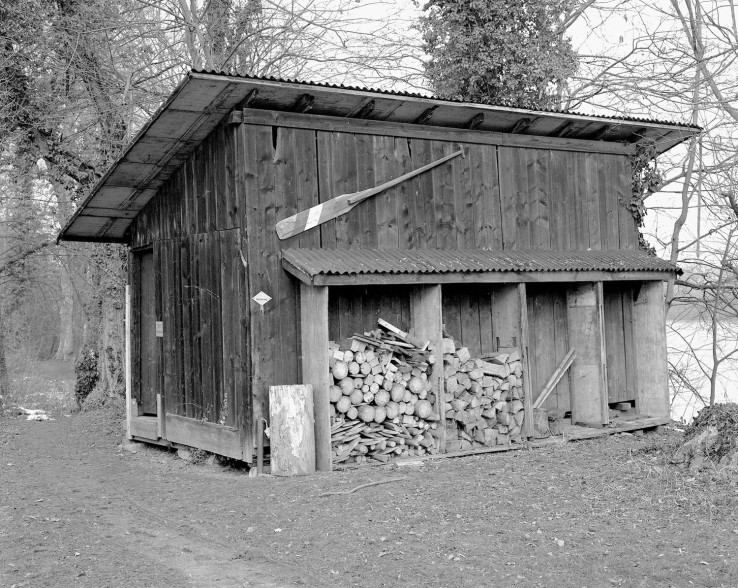

Wayne Roosa oriented our gathering by introducing us to two conceptual art projects by Simon Starling that offer opposing archetypes of the journey. The first, more aspirational one is Shedboatshed (Mobile Architecture No. 2), which involved the movement of a wooden shed from one Swiss riverside location to another. “This journey of 8 km downstream from Schweizerhalle to the centre of Basel was undertaken through the temporary mutation of the shed into a boat. This boat, a copy of a traditional Weidling, was made only with wood from the shed and was subsequently used as a transport system for the remaining parts of the structure. The shed already included an oar of the type used on Weidlings nailed to its facade as decoration. In its new location, the Museum für Gegenwartskunst, the boat was then dismantled and once again re-configured into its original form, but for a few scars left over from its life as a boat, it stands just as it once did several kilometres up-stream” [source].

“What I’m doing in a gallery situation,” says the artist, “is presenting a journey that I’ve been on, a process I’ve undertaken, and I’m asking for people to look at that in reverse. The circularity of many of the projects is a device to tell a story and it means that if you’re making a work about process, if you start and end in the same place, then somehow the journey becomes the important thing.” I think of lines from T. S. Eliot’s “Little Gidding”: “What we call the beginning is often the end / And to make an end is to make a beginning. / The end is where we start from”—and further down, “And the end of all our exploring / Will be to arrive where we started / And know the place for the first time.”

The second Starling work we considered was Autoxylopyrocycloboros, “a four-hour entropic voyage made across Loch Long [in Scotland] on a small wooden steamboat fuelled by wood cut piece-by-piece from its own hull.” This theatre of destruction ends with the boat’s debris floating—or sinking, as it were—in the water, Starling and his crewmate bobbing in their life vests somewhere out of frame. (The journey is presented in gallery settings as a series of thirty-eight color transparencies.) The title is an extrapolation of “ouroboros,” the mythical serpent who eats his own tail.

Roosa suggested that as we navigate the waters, we can either self-destruct, eating ourselves alive, or we can deconstruct and then reconstruct. As an organization, we ought to be committed to the latter—taking apart the structure we started with and putting it back together.

+++

Over two and a half days of conference, there were several artists’ panels that brought to the fore some truly exciting work. I especially enjoyed hearing artists Sedrick and Letitia Huckaby, a married couple, discuss their different artistic media, styles, content choices, and creative processes, and the way their work interacts with the other’s. Both explore themes of family, faith, and African American heritage.

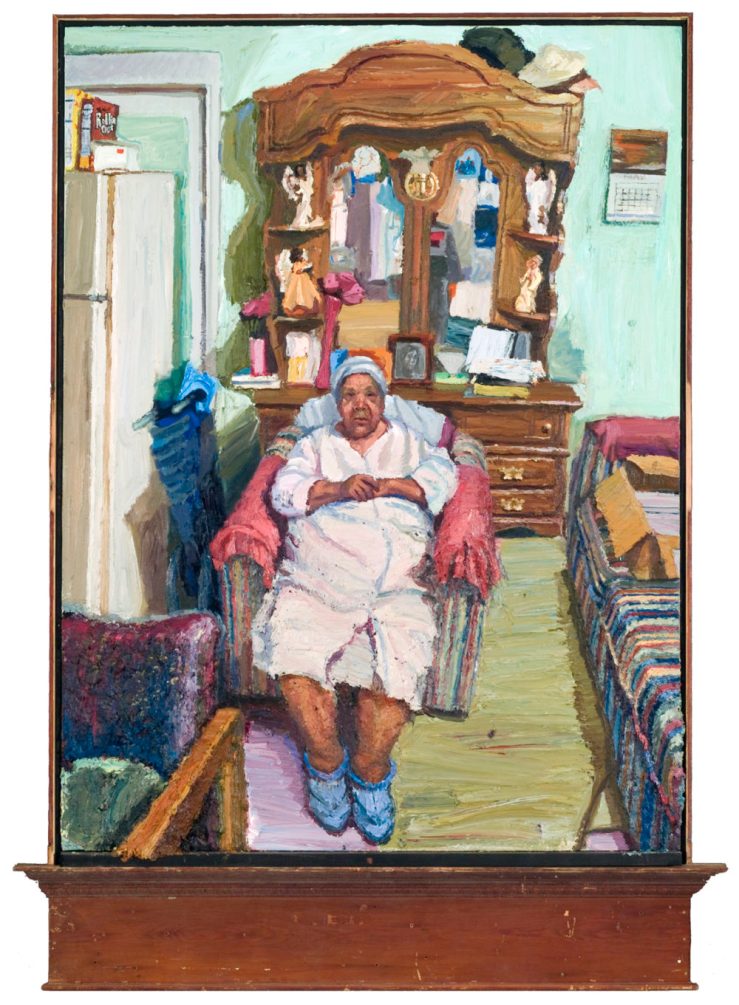

Sedrick Huckaby is a painter, draftsman, printmaker, and sculptor known for his portraits. His earliest body of work is a series of impasto paintings of his maternal grandmother, Hallie Beatrice Welcome Carpenter (“Big Momma”), inside her old wood-framed house in Fort Worth, Texas. These are so tender—they show her resting, drinking coffee, reading her Bible, getting ready for church, talking with family. After Big Momma died, he continued making in absentia portraits of her by depicting accessories she wore or household spaces that bear her imprint—The Shoes She Wore, The Altar Dresser. Sedrick is now renovating Big Momma’s house to serve as a creative project space for the neighborhood.

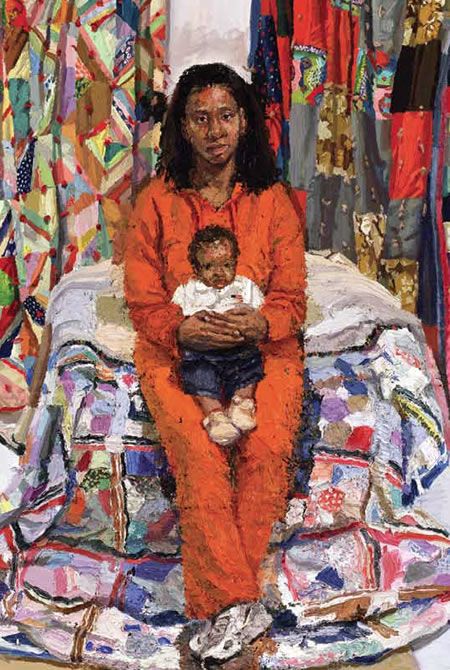

Family has long been the primary subject of Sedrick’s art. I love the 2006 portrait he painted of his wife seated at the foot of their bed and holding their firstborn son, Rising Sun. Mother and child are surrounded by family quilts, made by aunts and grandmothers. The opening between the two wall-hanging quilts forms a square halo around Letitia’s head.

Sedrick’s interest in portraiture extends to those outside his family. For the series A Dialogue with an Unknown People, he culled turn-of-the-century photographs from his local art museum that document African Americans from a small Kansas community, reproducing the proud figures in mixed media on paper beside a portrait of a contemporary African American sitter. Each double portrait links the two people across time.

Some of Sedrick’s more recent work has moved into three dimensions, such as the triptych-like If Perhaps by Chance, I Find Myself Encaged . . . , which shows the impact of prison on the family unit. It’s a hypothetical portrait of himself, Letitia, and their three children (one still in utero).

Quilts also feature heavily in Sedrick’s work. He said that while he used to paint them only as backdrops in his paintings, in grad school he realized that they were strong enough to be the main subject. Hence his eighty-foot, four-paneled painting A Love Supreme, whose various folds of brightly colored fabrics mimic the rhythms of John Coltrane’s spiritual jazz suite of the same title.

“Sedrick Huckaby has managed to stay true to himself, his family, and to a rigorous practice of lovingly recording the world he knows with great sincerity, revealing a depth of religious wisdom seldom found in contemporary art culture, laden as it often is with fashionable irony,” writes Bruce Herman. “His homage to the mothers of his community, to their great care and sacrifice, and his tough and painterly brand of realism point to a great love, a compelling vision of faith and yearning.”

Letitia Huckaby is a multimedia artist specializing in photography. Since childhood, she has been drawn to the Deep South—its land, its people, its history, its culture. Her father was from Greenwood, Mississippi, and her mother was from Louisiana, but Letitia grew up on military bases in Germany, and she only ever visited the South sporadically.

As a young adult she attended college in the US and spent time documenting, through photography, the places of her family’s southern roots, everything from cotton fields and bayous to roads and clotheslines, churches and sharecroppers’ homes. She then screen-prints these images on cotton fabric and hand-stitches them into quilts. One, for example, is made up of patches of Mississippi mud in a range of hues. Another, made after her father’s death, combines photographs of insect-ravaged cotton bolls with micrographs of impaired cells and glucose buildups; also part of the patchwork are silhouettes of family members and, in the center, herself, head bowed down against the backdrop of her dad’s obituary.

Letitia also prints photographs on vintage sacks used to hold sugar, flour, and picked cotton, as in her Suffrage series. Most people hear suffrage and think “right to vote,” and that’s one meaning of the term, but a suffrage is also a short intercessory prayer or petition. In Sugar and Spice, that prayer is multifaceted. It shows Letitia’s daughter Halle Lujah holding a sign that says ENOUGH. Letitia says this protest cry is from nine-year-old Yolanda Renee King’s March for Our Lives speech: “I have a dream that enough is enough, and that this should be a gun-free world. Period.” But in addition to being a suffrage for an end to gun violence, particularly school shootings, Sugar and Spice also prays for an end to racial injustice. The image evokes the iconic civil rights–era painting The Problem We All Live With by Norman Rockwell, which shows six-year-old Ruby Bridges integrating William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans, a racial slur graffitied on the wall behind her.

One of Letitia’s other series is Bayou Baroque. The subjects of these portraits are the African American Catholic nuns residing at the motherhouse of the Sisters of the Holy Family in New Orleans. Founded in 1842 in defiance of the plaçage system, the order continues to serve children, the elderly, and the poor to this day. Letitia described to us the women’s hesitance to be photographed—especially by an artist who was bringing floral bedsheets to the photo shoot! But they eventually warmed up. The subjects pictured below, Sister Canice and Sister Canisius, are biological sisters—twins, in fact. Letitia said they exhibited such a sweet closeness—they walked into the room holding hands. After photographing them, Letitia screen-printed the image on fabric and quilted it back together, setting the quilt inside a frame with a bedsheet matte that gives it depth.

Letitia said it’s important to her to really see those who tend to not get noticed, and to lift these people up in her work—to honor their stories, their histories. “I want to immortalize people in the community who are often neglected.” Sometimes that’s done using a more documentary approach, as above, and other times the portraits are less identifiable but nonetheless personal, as in her commission for the Highland Hills Branch Library in Dallas. Unveiled at the grand opening of the new building in 2014, this permanent installation surrounding the main entrance features colored and patterned glass panels with silhouettes of community members. (She gathered the silhouettes by hanging a sheet, casting people’s shadows on it, and then cutting those out and transferring them to glass.)

She said one of the boys was so proud to see his profile on public display, he brought all his friends to show them.

Further reading:

- Interview with the Huckabys, published in National Endowment for the Arts Magazine

- “Ecstatic Dislocation: The Art of Sedrick Huckaby” by Joe Milazzo

- “Living Fabric: Letitia Huckaby Talks to History” by Lawan Glasscock

+++

Also at CIVA, Chris Larson and Rico Gatson, who met at Bethel University as undergraduates thirty years ago, discussed their collaborative multichannel video installation The Raft, which debuted in 2015 at the Pierogi gallery in Brooklyn. “The piece is comprised of four projections on the walls of a room: one overhead camera of Larson and Gatson on a wooden ‘raft,’ two intimate cameras placed on and occasionally moved around the raft, and a final shot of the constantly flowing Mississippi River” [source]. The friends created the video in Gatson’s art studio over the course of eight hours, cut down to three in the final work. During this time they engage in musical dialogue, taking turns selecting and playing tracks from their respective record collections—everything from Billie Holiday and Mos Def to the Louvin Brothers and Bob Dylan—as their raft is pulled back and forth across the studio floor. View an excerpt.

The piece implicitly references The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, that great American novel about a poor white boy and a runaway black slave who travel down the Mississippi together on a makeshift raft. Like Twain’s novel, The Raft has to do with friendship as well as race (it’s hard to disentangle the two). For an excellent description of and commentary on the installation, read this Brooklyn Rail article by Sheila Dickinson.

+++

Joyce Yu-Jean Lee is a New York City–based artist working with video, digital photography, and interactive installation. Her art examines how mass media and culture shape notions of truth and understanding of the other. During a CIVA panel, she discussed her project Firewall, a popup internet café whose computer stations display split-screens that enable participants to simultaneously search the web in the US (using Google) and in China (using Baidu, China’s leading search engine). You can enter whatever you wish into either search bar, depending on your language skills, and a custom-coded plugin developed by Lee and Phiffer runs a side-by-side image search, displaying the results from each country.

Firewall premiered in 2016 at Chinatown Soup in Manhattan’s Lower East Side and has since visited Norway, Austria, and Hong Kong. One of the most popular searches is “Tiananmen Square”: Google reveals images of the 1989 massacre, including “Tank Man,” but Baidu only turns up scenic snapshots of the square. It’s also interesting to search Chinese political dissidents.

While demonstrating online censorship in China is certainly an objective of the art project, Lee said she also wants people to think about how some of the search results reflect different cultural values. For example, she noted that when you search “happiness,” Google results tie the word to the individual, to freedom (e.g., arms outspread on a mountaintop, or relaxed on a meditation cushion), but on Baidu “happiness” is always connected to family or romance.

+++

While at the conference, I attended a handful of breakout sessions. One was the presentation of an excellent paper by Sara Schumacher, a lecturer in theology and the arts at St. Mellitus College in London, titled “The Flourishing of the Artist and Church-as-Patron: A Theological Reflection on Contemporary Practice in the United Kingdom.” It centers on the collaboration between Old Saint Paul’s Episcopal Church in Edinburgh and the Scottish painter Alison Watt OBE in the creation of Still, a project that the artist, who is not a member of that church, initiated. Schumacher commends the partnership and final product as successful in all respects.

Still is a large four-paneled painting that hangs above the altar in the church’s WWI memorial chapel. Depicting draped white fabric that appears to be suspended in midair, it “suggests an absence that is strangely like a presence,” said Richard Holloway, chair of the Scottish Arts Council. A cross emerges from the negative space between the panels. “It’s put resurrection into the place of loss,” the church’s rector said.

This painting was new to me, and I really appreciated being given the chance not only to reflect with a small group on its theological and aesthetic qualities and its liturgical purpose but also to learn about the context of its coming to be, and how the congregation received it.

+++

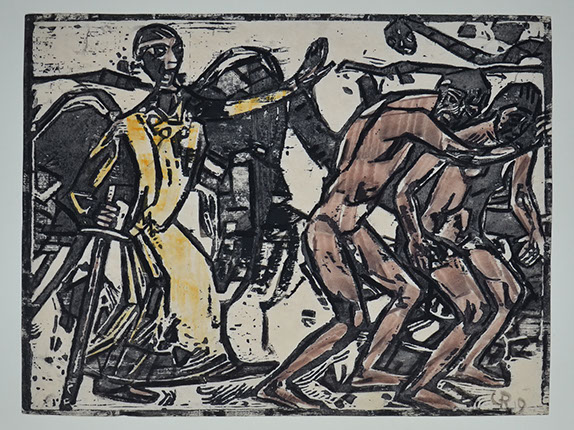

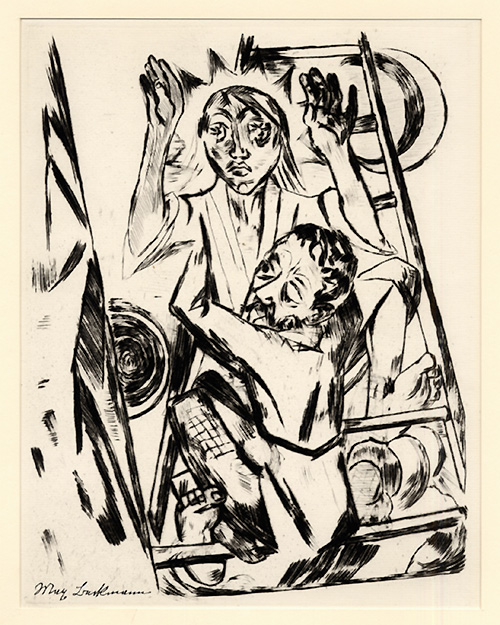

Another breakout session I participated in was led by Sandra Bowden, one of today’s foremost collectors of modern biblical art. She and Ed Knippers, a friend and fellow art collector and artist, discussed the exhibition Was God Dead? Biblical Imagination in German Expressionist Prints, a survey of sixty-one works from Sandra’s collection by such important artists as Max Beckmann, Lovis Corinth, Kathë Kollwitz, Otto Dix, Christian Rohlfs, Karl Schmidt-Rottloff, Wassily Kandinsky, and Edvard Munch, among others. The exhibition opened in January at Calvin University and is traveling the country, with six planned stops through March 2021. (If your church or institution would like to rent the exhibition, contact Sandra through her collections website. The rental fee is $1,000 for four weeks.) (Note: If you have trouble viewing the website in Chrome, try a different web browser.)

In the introduction to the exhibition catalog, Brent Williams writes,

The German Expressionists have garnered a reputation of brutal, harsh, and stark imagery depicting the difficulties of life resulting from World War I and its tumultuous aftermath. The visceral woodcuts, brooding and mysterious line work, and ominous lack of color serve to reflect the lens through which artists viewed the world around themselves.

But, even with Nietzsche’s vast influence on German expressionism and amid the aftermath the Great War and its traumas, artists still turned to the biblical story for inspiration, which they regarded not as dogma but as a “powerful depiction of the drama of the human condition and the ultimate meaning and integrity of human life in the face of human suffering that can preserve hope for social and cultural transformation through inner spiritual transformation,” writes Daniel A. Siedell in the catalog essay “German Expressionism and the Biblical Imagination: Historical and Cultural Context.” Old Testament themes of expulsion, wandering, and deliverance had particular appeal, as did narratives from the life of Christ, especially his passion. As Marxist philosopher Ernst Bloch wrote in Atheism in Christianity (1968), “The Christ-Impulse lives even when God is dead.”

I was actually surprised to find among these works biblical subjects that I wouldn’t have thought to associate with expressionism, including miracles, parables, acts of divine provision and praise—Elijah fed by ravens, the Adoration of the Magi, the Visitation, the miraculous catch of fish, the return of the prodigal son.

+++

One of my favorite CIVA traditions is what’s called the Late Late Show, where artists are given six minutes to present a body of work. Here are just a few artworks that stood out to me from the thirty-two artist presentations.

Marianne Lettieri, whose presentation from the 2015 CIVA conference I also fondly remember, shared the works she made for the traveling exhibition Making Good(s), a joint venture among CIVA; the Asbury Theological Seminary’s Office of Faith, Work and Economics; the Howard Dayton School of Business; and Asbury’s art department. Curator Keith Barker matched professional artists with student entrepreneurs for collaboration, based on an overlap of interests and/or opportunity for mutual inspiration—Marianne was paired with Seth Neckers, who ran a small-scale local free-range organic egg farm out of the Asbury Seminary Community Garden.

“My art often places mundane objects within religious architectural schemas and liturgical forms as a visual metaphor for seeing the sacred in the everyday,” Marianne said. In response to Seth’s enterprise, Marianne created several works, among them an old wooden cash register drawer in which egg forms are nestled in white cotton quilt batting; vinyl fried egg images adhered to the panes of a pointed arch window that was salvaged from a turn-of-the-century church; and, pictured below, Reliquary for Farmer, the “relics” inside the glass garden cloche being Seth’s work gloves and the red dirt of his farm, shaped together in the form of an egg along with hymnal pages and glinting candy wrappers. (The companion piece, Reliquary for Artist, creates a similar form out of Marianne’s work apron and sawdust from her studio; see “The Path of Vocation: Marianne Lettieri.”)

“The show’s theme is the commonality between artists and entrepreneurs who use their gifts to make goods that contribute to the common good,” Marianne said, and who both “venture into the unknown.”

Delro Rosco is an artist from Hawaii who shared in public for the first time his mixed-media series New Mornings, which consists of 140 works and counting. He has been making these small-scale pieces since last November as a way to work through his grief over having lost his mother. As part of his healing process, he regularly goes out to watch the sun rise over the beach near his home. His visual impressions of wave, sky, and sand—the washes of light and color over them and their movement—are put down on paper to serve as a remembrance of a morning spent awash in God’s gentle graces. Delro’s journey is toward the weeping prophet’s testimony of hope: “The steadfast love of the Lord never ceases; his mercies never come to an end; they are new every morning; great is your faithfulness” (Lam. 3:22–23).

I was just notified today that Delro has added images from the series to his website, which you have to check out: http://www.delroroscoart.com/694470/new-mornings-2018-2019/ (scroll right to view subsequent pages). I’m drawn to the openness and the beauty of these paintings that praise through pain.

Michelle Arnold Paine’s paintings also convey a sense of transcendence. They bear the influence of her ten-year sojourn in Italy, her Catholic faith, and her interest in painterly themes of mirror and window. A great deal of her work centers on the Virgin Mary and the Annunciation, which she sees as both a historical moment and a metaphor for how we open ourselves to God.

Reflections: On the Edge was part of the recent Divine Dimensions exhibition at 20 North Gallery in Toledo. Michelle writes,

The figure in the mirror is attentive, ready, waiting, poised in the act of creating. Her world is not limited to the objects before her – the mirror, the window, the branch. Within them, through them, she sees more: she sees deeper into a physical world than would be considered possible at first glance The play of light on the mirror reveals a view of herself from behind: a vision of her small world she cannot see with her eyes alone. The small room in which she works suddenly recedes into deep space. . . .

The waiting, creative pose of the woman and the light “overshadowing” the figure from the window both allude to the representation of another story, another woman who watched attentively, and met unexpected Truth in the presence of the mundane. The title “Reflections: On the Edge” alludes to this crossing over between heaven and earth that occurred in the Incarnation. . . . The images of the open door, the window, the light all point to dwelling on the edge between finite and infinite space the way Mary did.

Daniel Hendricksen’s Earth/Heaven, comprising two painted panels (one green, one blue) that fit together obliquely, references this same overlap, or point of connection, between realms.

Dan said this work was inspired in part by the writings of N. T. Wright (which also deeply influenced The Bible Project’s “Heaven and Earth” video). Take this excerpt from Wright’s Surprised by Hope, for example:

God and the world are different from one another but not far apart. There were and are ways in which, moments at which, and events through which heaven and earth overlap and interlock. . . . Heaven is not a faraway place we hope to go to someday. Through Christ it is very near, it is the control room of earth, and as we follow Jesus, the reality of heaven comes alive in us and is unleashed through us. Heaven and earth are overlapping realities and the resurrection of Jesus has connected these two spheres more closely than we know.

The slightly off angle at which Dan’s heaven and earth pieces come together suggests that the union between the two is presently imperfect but that God will one day fuse them together as one, as they were always meant to be.

Fascinated as I am by modern biblical imagery, I appreciated Anthony Santella’s artistic imagining of an angel, inspired by such passages as Isaiah 6, Ezekiel 1, and Revelation 4. His large painted wooden sculpture portrays this six-winged heavenly being as striking, even somewhat fearsome, a far cry from the chubby-cheeked baby angels to which we are accustomed, or even the humanoid ones. The eyes on the wings have precedent in medieval art—see, for example, the apse of Sant Pau de Esterri de Cardós, the stained glass of Chartres Cathedral, or the mosaics of Cefalù Cathedral in Sicily.

Justin Sorensen, whose solo show at Wesley Theological Seminary I saw last year, presented his new work, including A Secular Age, which I take as a comment on the indecision bred by the plenitude of religious options available today—and an unwillingness to commit to a singular path, to venture forth with any kind of strong conviction. The neon text reads, “Um um um um um.”

Christen Mattix shared her For Longing performance art project, which involved her knitting a half-mile blue line to connect an out-of-use bus stop bench in her neighborhood to Bellingham Bay. She began the project in May 2012 when she was new to the area and craving interaction. Every day for one hour, come rain or shine, from May through November, she sat at the bench with her yarn and needles. Naturally, people would follow the line with curiosity to its origin and, amused, start a conversation. Some people would bring her picnic meals, and one woman donated a hose reel for reeling in the knit string at end of day.

Over three years later, in August 2015, the string was complete. Christen hosted a closing celebration that was well attended by friends of all ages that she had made along the way. With these friends and neighbors, she secured one end of the string to the street-side bench and marched down to the water, where she dropped in the other end. She overestimated the distance by a few yards, so one man stripped down to his shorts, jumped in, and swam the rope out to its furthest extent to resounding cheers.

Christen said the real artwork was not the string but the people coming together in love and joy and support. The project, she said, was her way of knitting the community together and knitting herself into the community.

[…] More art from the 2019 CIVA conference and related activities is forthcoming in part two. […]

LikeLike

Much to enjoy in this blog — much to learn

Thanks!

LikeLike

Hello Victoria Emily Jones, I kick myself for missing the opportunity to meet you at the CIVA conference in June! I have for several years enjoyed receiving the wonderful posts and thoughtfulness with which you introduce your readers to such a wide range of work. And never in a million years would I think that my work would appear in the spotlight of your blog. I did a double take as I scrolled through reading this issue! Thank you for the gracious inclusion with the terrific artists who also presented at “Are We There Yet?”. I was so impressed with the quote you pulled up from Tom Wright’s book “Surprised By Hope” – a perfect fit with the painting. I had searched earlier for a quote – when I presented the piece at my home church’s annual Arts Festival. This quote was so perfectly distilled and to the point. I’m honored that you chose to include the piece “Earth/Heaven” in this portion of your round-up of memories from the conference. Your recounting of the events of those days brings back to life the energy and sense of purpose that I felt there. It’s because of your blog that I became aware of CIVA and joined, and really, I thank you most for that. I hope you continue to bless your “public” with your wide ranging searches and reflections on the works of all of God’s creative people!

Dan Hendricksen

>

LikeLike

[…] This is the final installment of a series on the Christians in the Visual Arts (CIVA) conference held June 13–16, 2019, at Bethel University. Photos are my own. [Read part 1 and part 2.] […]

LikeLike

[…] By way of example, he discusses the Tomb of Maria Magdalena Langhans (1723–1751), who died in childbirth, along with her baby, on Holy Saturday; the Memorial to Fallen Workers in Hamilton, Ontario; and Sugar and Spice by Letitia Huckaby [previously]. […]

LikeLike

[…] assertion of and call to common humanity, a better way. It’s life-affirming. As artist Laura Bon says: “Artists need to create on the same scale that society has the capacity to […]

LikeLike

[…] by Dr. Jonathan T. Pennington: In 1960 the German expressionist artist Otto Dix [previously] published Matthäus Evangelium, a cycle of thirty-three lithographs based on the Gospel of […]

LikeLike

[…] Thomas [here], Kehinde Wiley [here], Clementine Hunter [here], Letitia and Sedrick Huckaby [here]—plus twenty-six […]

LikeLike

[…] first is by my friend Marianne Lettieri [previously], whose work is informed by her “increased awareness of the enchantment of everyday actions and […]

LikeLike